OPPORTUNITIES

MOVE FOOD

FORWARD

© FAO/LUIS TATO YOUNG FARMERS VISITING A PIG FARM IN GATANGA, KENYA

02 The changing landscapes of youth opportunity

© FAO/LUIS TATO YOUNG FARMERS VISITING A PIG FARM IN GATANGA, KENYA

© FAO/MATEO ALFEREZ A YOUNG COCOA FARMER IN CUBARÁ, COLOMBIA.

KEY MESSAGES

- Nearly 85 percent of the world’s 1.3 billion youth live in lower-income countries, particularly in subSaharan Africa and Southern Asia, where their numbers continue to rise.

- Despite rapid urbanization, rural areas still accommodate 46 percent of the youth population. Inclusive rural transformation remains critical to improving youth welfare.

- Most rural youth live in regions with traditional and protracted crisis agrifood systems. Transforming these systems through inclusive productivity growth is crucial to improving their economic prospects.

- Countries with industrial agrifood systems, predominantly in Eastern Asia, Europe and Northern America, have lower shares of rural youth. These regions face labour shortages, necessitating strategies to attract and retain youth in the agrifood sector.

- Most rural youth live and work in areas with high agricultural productivity potential and moderate to high market access, offering varied opportunities for engagement in agrifood systems. However, 36 percent live and work in areas with strong agricultural productivity potential but weak market access, suggesting that in some contexts, improving infrastructure and market access may be more critical to enhancing youth livelihoods than boosting agricultural productivity alone.

- About 395 million rural youth live in areas facing climate change-induced declines in agricultural productivity potential. Climate resilience, social protection and migration options are pivotal to safeguarding their economic prospects.

- Youth are highly mobile, with higher rates of migration than adults, particularly within their own countries. Most youth migrants do not cross international borders. Nonetheless, international migration among youth aged 15 to 24 grew over the last decades from 22.1 million in 1990 to 31.7 million in 2020. Youth represent 16.2 percent of migrants in sub-Saharan Africa, and 15.2 percent in Latin America and the Caribbean.

- Youth migration is closely linked to other life transitions such as entering the workforce, pursuing higher education and marriage, with these transition patterns varying significantly by gender. Across all agrifood system types, female youth migrate internally at higher rates than their male peers, primarily for marriage and to join a family.

- Youth migration, particularly from rural to urban areas, is often temporary or seasonal, allowing youth to keep ties with rural areas, while exploring different livelihoods options.

INTRODUCTION

Youth engagement in agrifood systems and its outcomes are shaped by both the availability of opportunities and young people’s ability to access and leverage them effectively (see the conceptual framework in Chapter 1). These opportunities vary across context and are influenced by an area’s biophysical and socioeconomic conditions, the structure of agrifood systems and broader rural and structural transformation processes. Consequently, youth encounter a diverse set of challenges and possibilities related to participation in agrifood systems, depending on where they live. This chapter draws on data from multiple sources to map where young people live and examine the agrifood systems transitions that have taken place in these areas, in order to identify contextual opportunities for and constraints on youth engagement. It also discusses how the geographic distribution and migration patterns of youth influence labour availability for agrifood system transformation and explores the extent to which opportunities are susceptible to climate-induced shocks

Youth are highly mobile, often moving within and across regions in search of better economic opportunities. This mobility enables them to access diverse opportunity spaces, including urban and international job markets, higher education institutions and environments that support emerging and growing agrifood enterprises.1 Youth movement patterns can affect the redistribution of labour,1 knowledge and financial capital,1 which in turn can have implications for the resilience and sustainability of agrifood systems. Remittances from young migrants abroad often support agribusiness initiatives in their origin communities, while returning migrants bring new ideas, skills and technologies that can boost agricultural productivity and innovation.1 Youth migrants also play a crucial role in agrifood systems, especially in regions where the agriculture sector faces labour shortages.3–6 Evidence shows that both rural-bound7 and (peri-)urban-bound8, 9 migration convey important welfare benefits. To fully capture youth opportunities, the chapter also investigates the extent of youth mobility across geographies, the characteristics of mobile youth, the factors driving their migration and the constraints they encounter. Through this analysis, the chapter lays the foundation for understanding youth realities across different contexts and highlights how patterns of residence and mobility shape youth economic prospects and agrifood systems outcomes.

MAPPING WHERE YOUTH LIVE

This section draws on analyses integrating population data with high-resolution geospatial datasets to map where youth live. It applies the Urban–Rural Catchment Area (URCA) framework,10 which classifies rural and urban areas based on their travel time to urban centres and the population sizes of those centres. This approach enables cross-country comparability and offers a more nuanced view of market access and connectivity10, 11 (see Appendix 1 for details of the methodology). In addition, this section employs the agrifood systems typology (see Spotlight 1.1) and adapts the concept of rural opportunity space used in IFAD’s 2019 Rural Development Report12 to highlight how countries’ positions in terms of agrifood systems transition, together with local biophysical and socioeconomic conditions, shape contextual opportunities and challenges for youth engagement in agrifood systems.

DISTRIBUTION OF YOUTH POPULATIONS

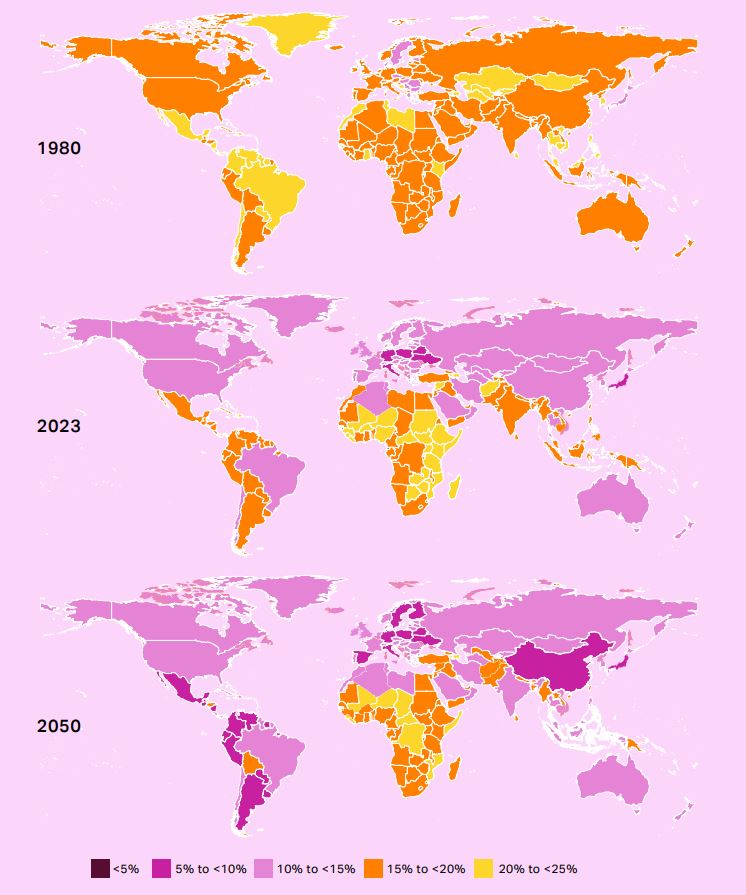

Globally, an estimated 1.3 billion individuals are between the ages of 15 and 24 years, the largest youth cohort in human history. While their proportion as a share of the global population is projected to decline in the coming decades (Figure 2.1), their absolute numbers will continue to rise, reaching approximately 1.4 billion by the early 2030s.13 However, youth demographic trajectories vary significantly across regions, reflecting differences in economic development, fertility rates and migration patterns. Two broad, divergent trajectories are evident. The first is found primarily in lower-income countries of regions such as sub-Saharan Africa and Southern Asia. Here, youth populations remain large and continue to grow due to high fertility rates and declining child mortality. Nearly 85 percent of the world’s youth live in these lower-income countries.13 Sub-Saharan Africa, in particular, has a higher-than-average share of youth among its population, and is expected to see a 65 percent increase, reaching around 400 million by 2050 (Figure 2.2), 13 Similarly, youth make up one in six people in regions such as Latin America and the Caribbean, North Africa, Southeast Asia, and Western and Central Asia. By the middle of the century, youth populations are expected to grow by 50 percent in Central Asia and 24 percent in North Africa.13

EIGHTY-FIVE PERCENT OF THE WORLD’S 1.3 BILLION YOUTH LIVE IN LOWER INCOME COUNTRIES.

The second demographic trajectory is evident in high and upper middle-income countries, primarily in East Asia, Europe, Northern America and parts of Latin America, where youth populations are shrinking and make up a smaller share of the total population (about 10 percent or less). This decline is driven largely by persistently low fertility rates, which in some cases have fallen below replacement levels. In these regions, immigration is expected to become a key driver of future population growth.14

FAO /EDUARDO SOTERAS IN KAPOETA, SOUTH SUDAN, A YOUNG FARMER COLLECTS VEGETABLES AT A FARM

Figure 2.1

YOUTH SHARES IN POPULATIONS ARE DECLINING OVER TIME ALTHOUGH ABSOLUTE NUMBERS CONTINUE TO RISE

Notes: Refer to the disclaimer on page ii for the names and boundaries used in this map. Dotted line represents approximately the Line of Control in Jammu and Kashmir agreed upon by India and Pakistan. The final status of Jammu and Kashmir has not yet been agreed upon by the parties. Final boundary between the Republic of Sudan and the Republic of South Sudan has not yet been determined. Final status of the Abyei area is not yet determined. A dispute exists between the Governments of Argentina and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland concerning sovereignty over the Falkland Islands (Malvinas).

Source: Author's own elaboration using population data from UNDESA. 2024.World Population Prospects – Population Division – United Nations. New York, NY. [Cited 1 January 2023]. https://population.un.org/wpp/downloadss

Figure 2.2

YOUTH POPULATION TRENDS VARY ACROSS REGIONS

Source: : Author's own elaboration using population data from UNDESA. 2024. World Population Prospects – Population Division – United Nations . New York, NY. [Cited 1 January 2023]. https://population.un.org/wpp/downloads

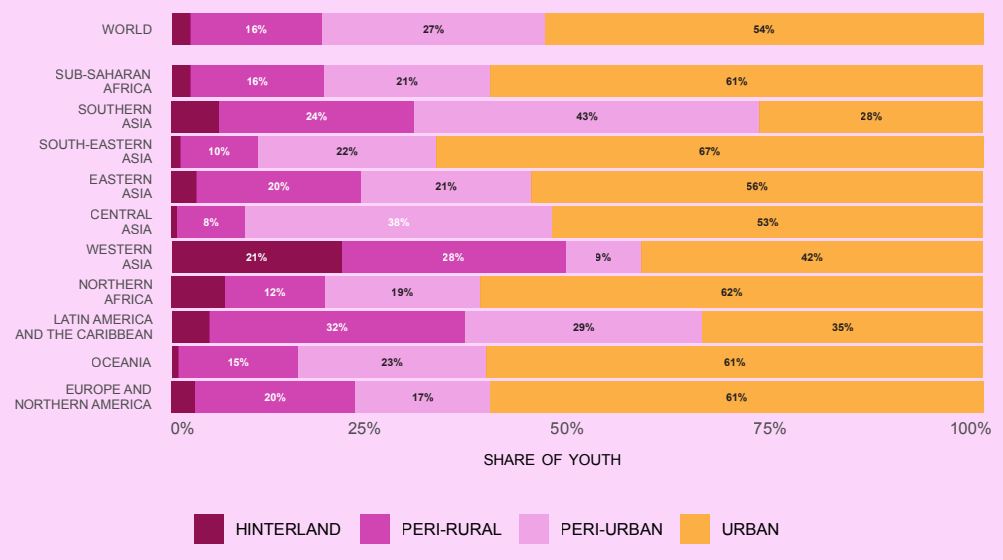

RURAL-URBAN DISTRIBUTION OF YOUTH

Urban areas host 54 percent of the global youth population, reflecting rising urbanization trends worldwide (see Appendix 1 for a definition of urban and rural spaces).15 This shift is driven by natural population increases, the expansion of small towns into urban areas, and rural-to-urban migration as young people seek better education and livelihoods, social mobility and cultural opportunities.15, 16 The shares of youth residing in urban areas are highest in South-eastern Asia (67 percent), North Africa (62 percent), Western Asia (61 percent), Europe and Northern America (61 percent), and Latin America and the Caribbean (61 percent). This trend reflects advanced urbanization and contexts in which youth engagement in agrifood systems will likely be more closely tied to off-farm segments of agrifood systems, especially retailing, food processing and services within urban and peri-urban areas, rather than primary agriculture.

Despite rapid urbanization, rural areas (consisting of periurban, peri-rural and rural hinterlands) still accommodate 46 percent of the global youth population. Although the proportions of rural populations and rural youth are expected to decline over time, projections indicate that about a third of the global population will continue to live in rural areas by the middle of the century.15 The allure of improved employment opportunities and services draws youth to urban centres, but a substantial share will likely stay and seek livelihood opportunities in rural areas due to factors such as family ties, cultural connections and opportunities in agriculture and entrepreneurship, and/or a variety of constraints that may limit mobility.17, 18 Young people may migrate temporarily to urban and peri-urban areas for work, but they often return to rural areas.19

NEARLY HALF OF ALL YOUTH (46 PERCENT) STILL LIVE IN RURAL AREAS.

More than half of rural youth (58.7 percent), representing about 27 percent of youth worldwide, are located in periurban areas, situated outside of city limits but within an hour’s travel to urban centres. These zones often blend urban and rural life,20 offering diverse economic activities, from agriculture to services and small industries.21, 22 Perirural areas host the second largest share of rural youth (35.4 percent), followed by rural hinterlands (5.8 percent). These areas are home to about 16 percent and 5 percent of the global youth population, respectively (Figure 2.3). Youth in peri-rural areas benefit from proximity to rural resources and urban markets, although their access to the latter is more limited than their peri-urban peers.23 Those in rural areas, and especially rural hinterlands, tend to maintain strong ties to their communities and traditional agricultural practices. This connection coupled with familiarity with local ecosystems positions them to innovate solutions that integrate traditional knowledge with modern technology in ways that are environmentally sustainable and socially acceptable.24 As demand for sustainable and locally sourced food continues to grow, youth in peri-rural and rural hinterlands are well-placed to capitalize on emerging opportunities in niche markets, such as organic farming.25, 26

Figure 2.3

A SUBSTANTIAL SHARE OF YOUTH RESIDE IN RURAL AREAS DESPITE RAPID URBANIZATION

Source: Author’s own elaboration based on population count estimates for 2020 from WorldPop( www.worldpop.org -School of Geography and Environmental Science, University of Southampton; the Department of Geography and Geosciences, University of Louisville; the Departement de Geographie, Universite de Namur); the Center for International Earth Science Information Network (CIESIN), Columbia University. 2018. Global High Resolution Population Denominators Project, funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (OPP1134076)(https://dx.doi.org/10.5258/SOTON/WP00647)and Cattaneo, Nelson and McMenomy. 2020. Urban-rural continuum. figshare. Dataset (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.12579572.v4).

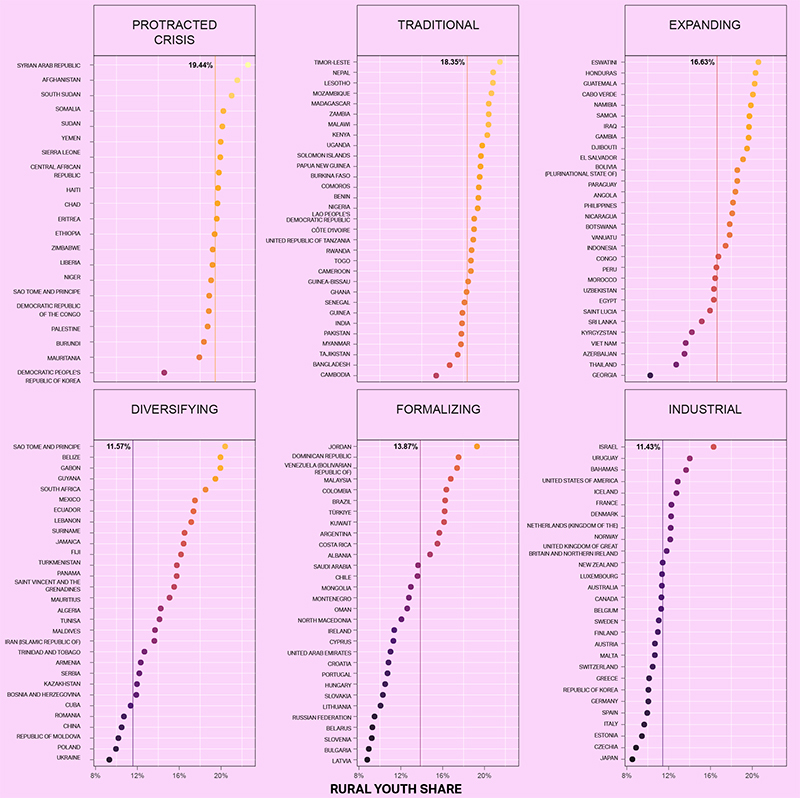

RURAL YOUTH DISTRIBUTION ACROSS AGRIFOOD SYSTEM TYPES

Agrifood systems transition is closely intertwined with youth demographic shifts, which present both challenges and opportunities for the long-term viability and resilience of agrifood systems. As countries transition from traditional, labour-intensive agriculture towards more diversified and industrialized agrifood systems, the share of youth in rural populations (Figure 2.4). and of rural youth and children in total population (Figure 2.5) declines. In the early stages of agrifood systems transition, as exemplified by countries with traditional and protracted crisis agrifood systems, youth make up a higher share of the rural population. Rural youth, on average, account for 19.4 percent and 18.3 percent of the rural population in countries with protracted crisis and traditional agrifood systems, respectively (Figure 2.4). These countries, mainly in Southern Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, collectively represent over half (55.3 percent) of the world’s rural youth.13 For countries with protracted crisis agrifood systems, rural children and youth below the age of 25 comprise 47 percent of the total population. Given their demographic profiles, these countries are unlikely to face labour shortages in the near term and instead have the potential to harness their large youth populations to drive agrifood systems innovation and rural transformation.

Figure 2.4

YOUTH SHARES IN RURAL POPULATION ARE HIGHEST IN COUNTRIES WITH PROTRACTED CRISIS AND TRADITIONAL AGRIFOOD SYSTEMS

Notes: Numbers indicated in black at the top of each panel refer to the average population of youth for the respective agrifood system type.

Source: Author’s own elaboration based on population count estimates for 2020 from WorldPop( www.worldpop.org -School of Geography and Environmental Science, University of Southampton; the Department of Geography and Geosciences, University of Louisville; the Departement de Geographie, Universite de Namur); the Center for International Earth Science Information Network (CIESIN), Columbia University. 2018. Global High Resolution Population Denominators Project, funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (OPP1134076)(https://dx.doi.org/10.5258/SOTON/WP00647)and Cattaneo, Nelson and McMenomy. 2020. Urban-rural continuum. figshare. Dataset (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.12579572.v4).

Figure 2.5

COUNTRIES IN EARLY STAGES OF AGRIFOOD SYSTEMS TRANSITION HAVE LARGE SHARES OF RURAL YOUTH IN THEIR POPULATIONS

Notes: Three letter abbreviations are ISO Alpha-3 codes. For a full list please see: https://unstats.un.org/unsd/methodology/m49/

Source: Author's own elaboration based on data on the share of rural population aged 0–24 out of the total population in 2015 from ILOSTAT (“Population by sex, 2age and rural/urban areas – UN estimates, July 2024 (thousands)”)27 and the agrifood systems ranking from Quinn et al.28 Data on the youth population in 2050 is indicated into parentheses and come from UNDESA. 2024. World Population Prospects – Population Division – United Nations. New York, USA. [Cited 19 February 2025]. https://population.un.org/wpp/downloads A value of zero indicates that the youth population in 2050 is less than 1 million. Design adapted from IFAD’s 2019 Rural Development.12

In contrast, countries in the later stages of agrifood systems transition, largely in Europe, Northern America and parts of East Asia and Latin America, collectively account for about 37 percent of the world’s rural youth, a relatively lower proportion averaging 11.5 percent, 13.9 percent and 11.4 percent in diversifying, formalizing and industrial agrifood systems, respectively (Figure 2.4). These substantially lower shares reflect broader trends of urbanization and increasing off-farm and non-agrifood system employment opportunities as agrifood systems transition.

Meanwhile, in countries with industrial agrifood systems, rural children and youth below 25 years of age account for only 5 percent of the total population, leading to growing risks of labour shortages and aging rural workforces. These economies, having undergone significant diversification, also offer more non-agrifood system employment opportunities, increasing competition for the shrinking pool of youth labour (see Spotlight 1.1). Without deliberate strategies to make agricultural careers more appealing, these countries will struggle with labour shortages, rising production costs and declining productivity, increasing the strain on existing workers. They also risk stagnation, higher dependence on migrant labour and potential disruptions in food supply chains, which could hinder the sector’s ability to adapt to evolving consumer demand, respond to environmental challenges and ensure sustainable food production. These challenges are particularly concerning for labourintensive agricultural sectors such as horticulture, where mechanization is not always feasible. Evidence from industrialized and formalizing economies suggests that agricultural labour shortages are already emerging as a pressing issue in some countries, with the agriculture sector relying on migrant workers to address these shortages.

MANY RURAL YOUTH LIVE IN AREAS WITH HIGH AGRICULTURAL POTENTIAL BUT POOR MARKET ACCESS.

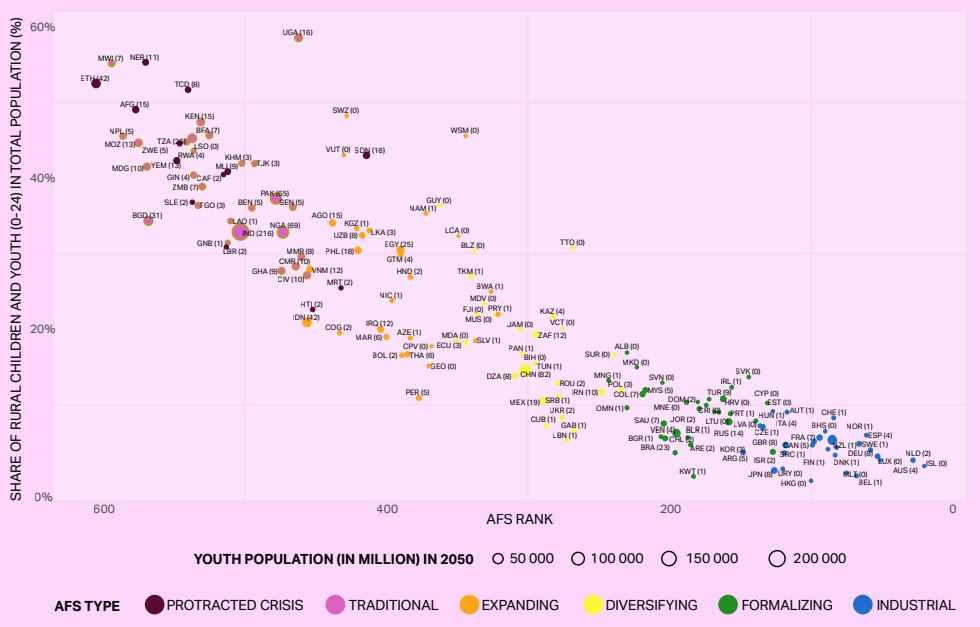

OPPORTUNITIES FOR RURAL YOUTH BY AGRIFOOD SYSTEMS TYPE AND LOCAL CONTEXT

The nature of agrifood systems transition in the areas where youth live influences the opportunities available to them. These distinct opportunities reflect a complex interplay of economic, social, institutional and environmental factors. As agrifood systems evolve, both new opportunities and challenges for youth arise at different stages of the transition. This dynamic is particularly apparent when examining how youth are distributed across agrifood system types and subnational “opportunity spaces” delineated by varying combinations of agricultural productivity potential and market access conditions (connectivity potential) (see Figure 2.6 and Appendix 1 for the methodology).

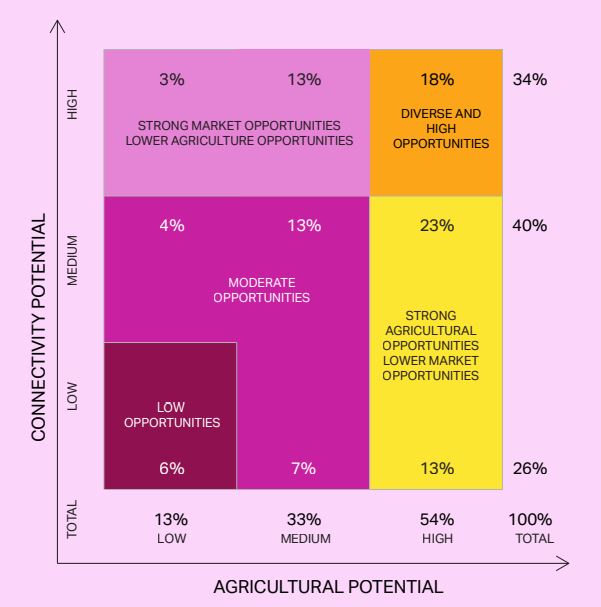

Most rural youth are located in areas with favourable agricultural productivity potential. About 54 percent live in high potential zones, 33 percent in medium potential zones and 13 percent in low potential zones Figure 2.6. This distribution reflects historical migration patterns, with populations gravitating towards areas offering better prospects for agriculture-based livelihoods.13, 15 However, residing in areas with high potential agricultural productivity – measured solely on biophysical and climatic conditions – does not necessarily translate into access to or benefit from that land, given prevailing barriers such as restrictive social norms and inheritance regimes, land rights and financial constraints (see Chapter 3).12

While most rural youth live in areas with strong agricultural potential, connectivity, defined by access to market, infrastructure and services, poses a greater constraint. Only 34 percent reside in high connectivity areas compared with 40 percent in medium connectivity areas and 26 percent in low connectivity areas – twice the proportion of those in low agricultural productivity potential zones Figure 2.6. The largest single share of rural youth (36 percent) is found in areas with strong agricultural productivity potential but weak market access Figure 2.7. These findings suggest that addressing infrastructure and market access challenges may be more critical to enhancing youth livelihoods than agricultural potential alone.

Figure 2.6

MOST RURAL YOUTH LIVE IN AREAS WITH STRONG AGRICULTURAL POTENTIAL AND MODERATE CONNECTIVITY

Notes: Rural areas include peri-urban areas, peri-rural areas and hinterlands

Source: Author’s own elaboration adapting the rural opportunity space framework12 and based on population count estimates for 2020 from WorldPop(www.worldpop.org -School of Geography and Environmental Science, University of Southampton; the Department of Geography and Geosciences, University of Louisville; the Departement de Geographie, Universite de Namur; the Center for International Earth Science Information Network (CIESIN), Columbia University. 2018. Global High Resolution Population Denominators Project, funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (OPP1134076).(https://dx.doi.org/10.5258/SOTON/WP00647) and Cattaneo, Nelson and McMenomy. 2020. Urban-rural continuum. figshare. Dataset (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.12579572.v4). cell tower (OpenCelliD https://opencellid.org cultivation potential (FAO and IIASA. Global Agro Ecological Zones version 4 (GAEZ v4) ) www.fao.org/gaez).

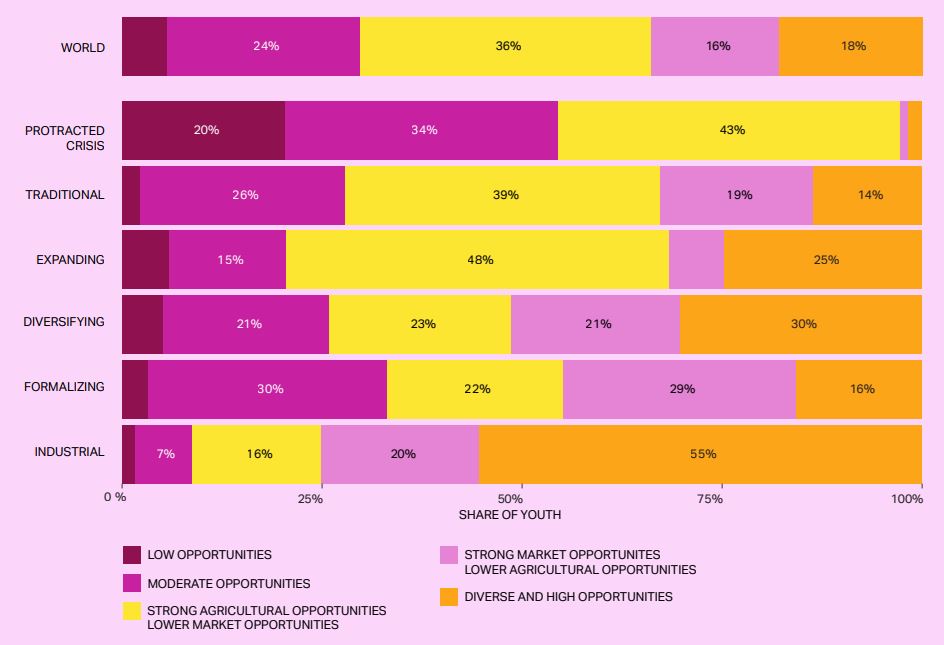

Across agrifood system types, opportunities for rural youth vary significantly, reflecting different stages of transition and broader structural conditions. Countries in advanced stages of agrifood systems transition offer the most diverse and high-quality opportunities for their rural youth. In industrial agrifood systems, 55 percent of rural youth reside in areas with both high agricultural productivity potential and strong market access conditions, while only 2 percent live in areas with low opportunities (Figure 2.7).

In contrast, youth living in countries in the early stages of agrifood systems transition (protracted crisis and traditional agrifood systems) face the most severe constraints. 28 These include most countries in sub Saharan Africa, North Africa and Western Asia. In protracted crisis contexts, about 20percent of rural youth reside in low opportunity areas characterized by limited agricultural productivity potential and market access. Only 2 percent live in areas offering diverse and high opportunities. Most youth (43 percent) inhabit and work in areas with strong agricultural productivity potential but limited market access, often exacerbated by conflict, instability and resource constraints. 12, 29 Countries with traditional agrifood systems present similar patterns, but with a larger share of youth (14 percent) living in areas with diverse and high opportunities (Figure 2.7). 30-32

Figure 2.7

RURAL YOUTH OPPORTUNITIES ARE HIGHEST IN INDUSTRIAL AGRIFOOD SYSTEMS AND MOST CONSTRAINED IN PROTRACTED CRISIS AND TRADITIONAL SYSTEMS

Source: Author’s own elaboration adapting the rural opportunity space framework12 and based on population count estimates for 2020 from WorldPop (www.worldpop.org - School of Geography and Environmental Science, University of Southampton); the Department of Geography and Geosciences,

University of Louisville; the Departement de Geographie, Universite de Namur); the Center for International Earth Science Information Network (CIESIN), Columbia University. 2018. Global High Resolution Population Denominators Project – funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (OPP1134076) (https://dx.doi.org/10.5258/SOTON/WP00647) and Cattaneo, Nelson and McMenomy. 2020. Urban-rural continuum. figshare. Dataset (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.12579572.v4). cell tower (OpenCelliD https://opencellid.org cultivation potential (FAO and IIASA. Global Agro Ecological Zones version 4 (GAEZ v4) ) www.fao.org/gaez).

Countries at intermediate transition stages characterized by expanding, diversifying and formalizing agrifood systems offer a more mixed picture. Predominantly located in Latin America, South-eastern, Southern and Eastern Asia, these contexts have higher shares of rural youth in areas with diverse and high opportunities and may offer a broader range of livelihood options across onfarm and off-farm segments of agrifood systems relative to traditional or protracted crisis agrifood systems.3

CLIMATE CHANGE AND RURAL YOUTH PROSPECTS

Agrifood systems are highly susceptible to environmental degradation and the multifaceted impacts of climate change,33,34 both of which are expected to amplify variability in agricultural production and affect agricultural productivity (see also Chapter 6).24 These changes could adversely impact economic opportunities in rural spaces.

To understand how variability in climate would affect young people’s economic prospects, current agricultural productivity potentials in the areas where youth live were compared with future projections derived from climate models. The analysis first identified regions undergoing climate change induced shifts in agricultural productivity potential. The total land cover and number of rural youth residing in these areas and their relative shares were then estimated for each of these regions.

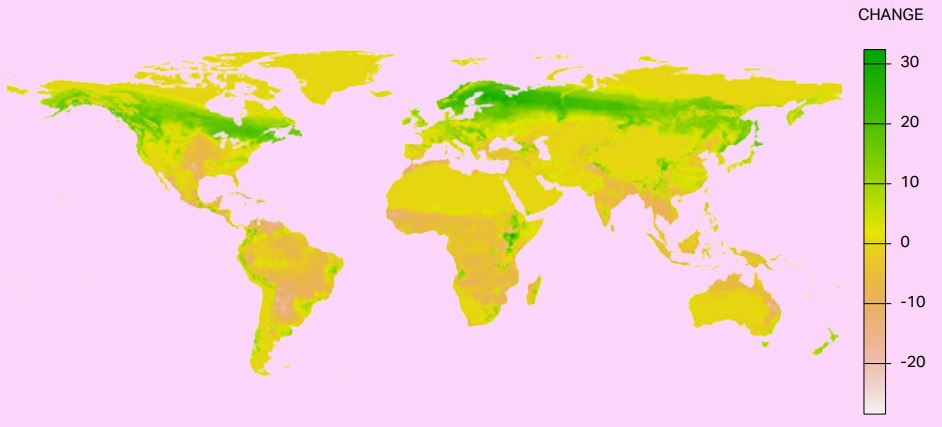

CLIMATE CHANGE UNEVENLY SHAPES GLOBAL AGRICULTURAL POTENTIAL

While projected shifts in agricultural productivity suggest that climate change will reshape food production potential worldwide, the benefits will be unevenly distributed. The modelled scenario projects a net gain of approximately 182.6 million hectares of land with improved productivity potential. However, this net increase does not account for associated risks, including extreme weather events, prolonged droughts and widespread wildfires, which could undermine the reliability of existing and newly viable agricultural lands for long-term food production.33,34

Significant regional disparities will emerge. The northern hemisphere, particularly Europe and Northern America, is expected to see productivity gains, with localized decreases in parts of the eastern coast of Australia, the Mediterranean coastline and the central United States of America (Figure 2.8). In contrast, large declines are projected across Latin America and the Caribbean, South America, sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia and Southeast Asia. While new areas may become for long-term food production.35 more viable for agriculture these are often sparsely populated, whereas declines will affect regions that currently sustain large populations, intensifying food security challenges.

Figure 2.8

CLIMATE CHANGE IS EXPECTED TO IMPACT AGRICULTURAL PRODUCTIVITY POTENTIAL UNEVENLY ACROSS THE GLOBE

Notes: Refer to the disclaimer on page ii for the names and boundaries used in this map.

Source: Author’s own elaboration using historical and estimated crop cultivation potential based on the IPSL-CM5A-LR model and the RCP 8.5 scenario – a high-emissions trajectory – spanning 2040 to 2070 (FAO and IIASA. Global Agro Ecological Zones version 4 (GAEZ v4)) www.fao.org/gaez)47 Climate change projection simulate the effects of anticipated climatic changes, highlighting the potential challenges posed to agricultural systems under continued high emissions.

CLIMATE-DRIVEN PRODUCTIVITY DECLINES AND RURAL YOUTH OPPORTUNITIES

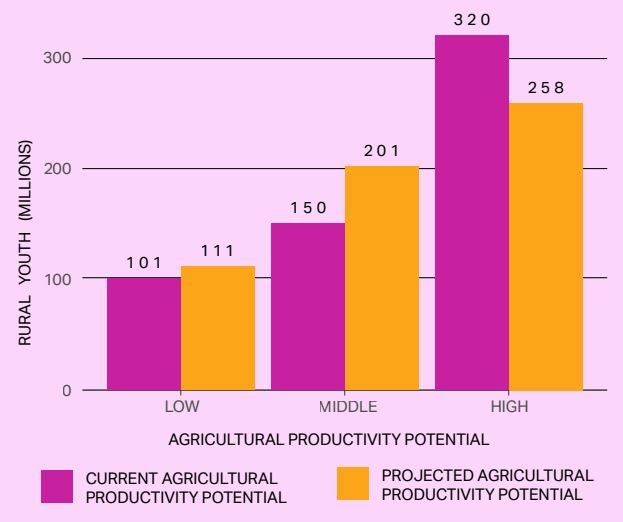

An estimated 395 million rural youth, representing about 69 percent of the global rural youth population, currently reside in regions projected to experience declines in agricultural productivity potential due to the adverse effects of climate change. Among them, about 111 million live in areas expected to experience low agricultural productivity potential – a 10 percent increase from a scenario without climate change. At the same time, the number of rural youth in high productivity areas is projected to decline by 19 percent due to climate change (Figure 2.9).

AROUND 395 MILLION RURAL YOUTH ARE EXPECTED TO FACE CLIMATE-INDUCED DECLINES IN AGRICULTURAL PRODUCTIVITY.

Figure 2.9

MANY RURAL YOUTH LIVE IN AREAS PROJECTED TO EXPERIENCE DECLINES IN AGRICULTURAL PRODUCTIVITY POTENTIAL DUE TO CLIMATE CHANGE

Source: Author's own elaboration based on population count estimates for 2020 from WorldPop (www.worldpop.org -School of Geography and Environmental Science, University of Southampton; the Department of Geography and Geosciences, University of Louisville; the Departement de Geographie, Universite de Namur); the Center for International Earth Science Information Network (CIESIN), Columbia University. 2018. Global High Resolution Population Denominators Project, funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (OPP1134076) (https://dx.doi.org/10.5258/SOTON/WP00647) and Cattaneo, Nelson and McMenomy. 2020. Urban-rural continuum. figshare. Dataset (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.12579572.v4); and crop cultivation potential (FAO and IIASA. Global Agro Ecological Zones version 4 (GAEZ v4) www.fao.org/gaez).

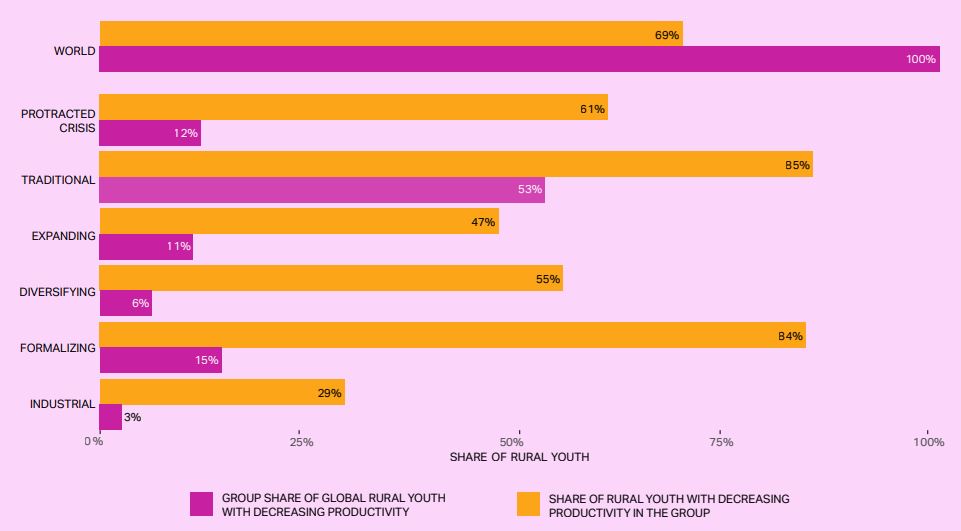

UNPACKING YOUTH MOBILITY Disaggregated analysis by agrifood systems typology reveals stark disparities in rural youth vulnerability to climate-induced declines in agricultural productivity potential. These differences reflect the interaction of climate risks, weaknesses in how agrifood systems operate and resource inequalities across different regions. Traditional agrifood systems are the most vulnerable, with 85 percent of rural youth in these systems – representing 53 percent of the global rural youth population – facing declining agricultural productivity potential (Figure 2.10). Two-thirds of rural youth in sub-Saharan Africa and 82 percent in Western Asia reside in areas projected to experience significant declines (Figure A5.1 in Appendix 5). In sub-Saharan Africa, in particular, limited infrastructure, outdated technologies and restricted access to adaptation resources leave rural youth ill-equipped to adapt.12, 37 In such circumstances, migration – whether voluntary or forced – can become inevitable.38 Over 9 million additional rural youth living in areas with low agricultural potential will further exacerbate these challenges. Rural youth in agrifood systems at intermediate stages of transition also face heightened vulnerability. Approximately 84 percent of youth in formalizing and 55 percent in diversifying agrifood systems are projected to experience declining productivity potential.

Figure 2.10

RURAL YOUTH LIVING IN TRADITIONAL AGRIFOOD SYSTEMS ARE MOST IMPACTED BY EXPECTED DECLINING PRODUCTIVITY FROM CLIMATE CHANGE

Source: Author's own elaboration based on population count estimates for 2020 from WorldPop (www.worldpop.org -School of Geography and Environmental Science, University of Southampton; the Department of Geography and Geosciences, University of Louisville; the Departement de Geographie, Universite de Namur); the Center for International Earth Science Information Network (CIESIN), Columbia University. 2018. Global High Resolution Population Denominators Project, funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (OPP1134076) (https://dx.doi.org/10.5258/SOTON/WP00647) and Cattaneo, Nelson and McMenomy. 2020. Urban-rural continuum. figshare. Dataset (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.12579572.v4); and crop cultivation potential (FAO and IIASA. Global Agro Ecological Zones version 4 (GAEZ v4) www.fao.org/gaez).

In contrast, rural youth in industrial agrifood systems, primarily in Europe and Northern America and parts of East Asia, are the least affected. Only 29.1 percent of youth in these systems are projected to experience impacts, representing 2.7 percent of the global total of affected youth. In some areas, climate change may improve agricultural productivity potential, reducing or forced – can become inevitable.35 Over 9 million the number of youth in low-productivity regions. The disparities in youth vulnerability across regions and agrifood systems typologies underline systemic inequality in exposure to climate risks.

UNPACKING YOUTH MOBILITY

Youth are historically willing to migrate in search of better opportunities and/or for reasons related to work, education or family decisions.39 This mobility enables them to access new areas, livelihoods and resources,40 particularly when opportunities in their place of origin are limited or declining.41,42 However, many young people face significant challenges to migration, including high financial costs, constraining social norms, lack of information, and limited access to networks or support systems in destination areas. Youth may also be reluctant to leave due to cultural and social ties.43 Youth migration can bring valuable skills and help fill labour gaps in destination areas, but when movements are unmanaged, they can strain the infrastructure and services of host communities, limiting young migrants’ access to decent employment. Understanding the potential and the limitations of youth mobility is key to designing inclusive policies and programmes – both at origin and destination – that can expand youth opportunities and support resilient and inclusive agrifood systems transition (see Chapter 7).

Youth engage in various types of migration including temporary, cyclical or seasonal movements. Migration can be internal (within their own country) or international (abroad) and undertaken alone or with family, and through regular or irregular channels. Many migrants move multiple times throughout their lives.44 Internal and international migration are often linked, as migrants tend to move in phased steps, from villages to towns or cities, and then internationally.45 This section examines patterns of youth migration – defined as the movement of young people away from their place of usual residence, either across an international border or within a state,46 exploring its types, drivers and associated opportunities and challenges.

INTERNATIONAL AND REGIONAL MIGRATION

Over recent decades, the number of international migrants has increased significantly, reaching 304 million in 2024,47 with corresponding increases in remittances to low- and middle-income countries projected to reach USD 685 billion in the same year.48 Youth migration has also grown, with the number of international migrants aged 15–24 rising from 22.1 million in 1990 to 31.7 million in 2020. However, their share out of total migrants declined from 14.4 percent to 11.3 percent over the same period,49 due in part to longer life expectancy among older migrants and migration policies that restrict access for lower-skilled migrants, who tend to be younger.14,50,51

The share of youth among international migrants varies across regions. Youth account for 16.2 percent of the total migrant population in sub-Saharan Africa and 15.2 percent in Eastern and Southeastern Asia and Latin America and the Caribbean, but only 9.2percent in Europe and Northern America. Youth aged 20–24 account for the majority of migrants (19 million or 6.8 percent of the total migrant population), compared to those aged 15–19 (12.5 million or 4.5 percent).49 Young women represent nearly half of international youth migrants (48 percent), with higher shares in sub-Saharan Africa (52 percent) and Eastern and Southeastern Asia, as well as Latin America and the Caribbean (51 percent).49

The share of international youth migrants residing in low- and middle-income countries (43 percent) is larger than that of older migrants (37 percent aged 25–34 and 30 percent aged 35–44).50 This trend may reflect in part the broader demographic reality that the majority of the world’s youth live in low- and middle-income countries. However, it also highlights a key characteristic of global migration – most international migrants, including youth, tend to move within their own regions. Europe has the highest intra-regional migration share (74 percent), followed by sub-Saharan Africa (64 percent). Youth migrants are more likely than older cohorts to choose regional destinations due to geographic proximity, lower migration costs, and strong cultural, linguistic and economic ties.50,52 Some regions such as Central and Southern Asia experience large migrant outflows, with 78 percent of migrants residing outside their region, particularly in member states of the Gulf Cooperation Council. Similarly, 60 percent of migrants from Latin America and the Caribbean live in Northern America, their movement contributing to one of the largest global migration corridors, although growth has slowed in recent years.49 Crucially, children and youth make up a large share of forcibly displaced populations, including refugees, asylum seekers and internally displaced persons (see Box 2.1).

Box 2.1

FORCED DISPLACEMENT

Children and youth represent a significant portion of the forcibly displaced (internally displaced persons, refugees, asylum seekers and other people in need of international protection). At the end of 2023, an estimated 117.3 million people worldwide were forcibly displaced due to persecution, conflict, violence or human rights violations, of which 68.3 million were internally displaced.i Some 40 percent of the forcibly displaced are under the age of 18.i According to the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC), in 2021, some 33 million children and young people under the age of 25 were internally displaced, of which 25.2 million were under the age of 18, and 11.4 million were between the ages of 15 and 24.ii Most refugees remain close to their countries of origin, with 69 percent hosted in neighbouring countries. Low- and middle-income nations continue to host three-quarters of the world’s refugees.i

Children and youth face heightened risks during displacement, including exposure to violence, abuse and disruption of critical developmental milestones such as education. Girls are particularly vulnerable to these risks, as displacement often exacerbates barriers to education and increases the risk of sexual violence. The long-term consequences of displacement, if unaddressed, can have a lasting impact, limiting future opportunities and perpetuating cycles of vulnerability. Addressing the specific needs of youth and children – such as healthcare (including vaccinations), education and vocational training – is essential to mitigating these risks, boosting their resilience and supporting their development.iii

Notes: Refer to the Notes section for full citations.

ASPIRATIONS AND PLANS TO MIGRATE INTERNATIONALLY

Youth express higher aspirations for international migration than adults across all agrifood systems typologies, with aspirations rising between 2015 and 2023 (Figure 2.11). In 2023, 46.6 percent of male and 45.5 percent of female youth expressed a desire to migrate compared to approximately 36 percent in 2015. Migration aspirations among youth are lowest in industrial agrifood systems and highest in countries with protracted crisis agrifood systems, where 61.8 percent of young males aspire to migrate (Figure 2.11) (see also Box 2.2). In such fragile contexts, such as Eritrea, where economic prospects are limited, youth often view migration as the only pathway to a better life.53 However, many young people may be unable to migrate due to financial and institutional barriers, and remain trapped in their present circumstances.5

In protracted crisis and traditional agrifood systems, male youth are more likely than female youth to aspire to migrate internationally, reflecting gender norms that favour men’s work outside the home.55 However, in other agrifood systems, migration aspirations do not differ notably by gender.

Despite high aspirations, few youth actively plan to migrate in the next year and even fewer have made concrete preparations for such moves (Figure 2.12; Information about plans and preparations to migrate internationally were only collected in 2015 Gallup World Poll data). This gap between aspirations and actual plans to migrate likely reflects the significant barriers young people face, including financial constraints, limited access to information and restrictive migration policies that limit migration opportunities.40 In addition, young people may hold aspirations to migrate internationally for years, but the period of active preparation could be much shorter. Changes in conditions at destination, including labour demands and migration policy shifts towards border restrictions or the opening of legal pathways for migration, can also influence if and when migration aspirations transform into actual migration.40 Key drivers of international and internal migration among youth are discussed later in the chapter.

© IFAD/LAISIASA DAVE/ PACIFIC FARMER ORGANIZATIONS IN NAVOSA, FIJI, YOUNG FARMER FILIPE BAITUWAWA IS GROWING NUTRITIOUS VEGETABLES FOR HIS COMMUNITY, AFTER RECEIVING TRAINING AND FARMING INPUTS TO BOOST LOCAL FOOD SECURITY DURING THE COVID-19 LOCKDOWN

Figure 2.11

THE SHARE OF YOUTH ASPIRING TO MIGRATE INTERNATIONALLY INCREASED BETWEEN 2015 AND 2023 ACROSS MOST AGRIFOOD SYSTEM TYPES

Source: Author’s estimates based on Gallup World Poll datasets for 2015 and 2023. The estimates are unweighted averages derived from pooled survey data across different agrifood system typologies. The plots show the proportion of individuals who aspire to migrate across different agrifood system typologies based on pooled survey data from over 120 countries for the years 2015 and 2023. The agrifood systems typology averages are derived by computing the weighted mean of migration aspirations within each typology, ensuring representation across all included countries. The world average is similarly computed by pooling all countries together, providing a global estimate of migration aspirations. The estimates were produced using adjusted survey weights following Heckert et al.56

Figure 2.12

ASPIRATIONS TO MIGRATE INTERNATIONALLY ARE HIGHEST AMONG YOUTH, ESPECIALLY IN PROTRACTED CRISIS SYSTEMS, BUT RELATIVELY FEW HAVE MADE PLANS OR PREPARATIONS TO MIGRATE IN THE NEXT 12 MONTHS

Note: The figure shows the share of youth who aspire to migrate, plan to migrate or have made preparations to migrate in the next 12 months, disaggregated by sex and agrifood system typology.

Source: Author's estimates using the Gallup World Poll dataset for 2015. The estimates were produced using adjusted survey weights following Heckert et al.56

YOUTH MIGRATION WITHIN NATIONAL BORDERS

While international migration often receives the most attention, the majority of migration occurs within national borders,45 especially among youth, who typically lack the financial resources and networks necessary to migrate internationally.

Box 2.2

YOUTH MIGRATION TO EUROPE – MIGRANT CHARACTERISTICS AND KEY MIGRATION DETERMINANTS

In 2023, the International Organization for Migration (IOM) published data capturing the experiences of migrants aged 14–24 travelling to Europe by sea and land. These journeys, often perilous, reflect young individuals’ aspirations for better futures as well as their need to escape crises or violence in their home countries. The data were gathered using the Displacement Tracking Matrix (DTM), a set of tools developed by IOM to gather and analyse information on the mobility, vulnerabilities and needs of mobile and displaced populations.

Young migrants came from a diverse range of countries, of which Afghanistan (15 percent), Morocco (12 percent), Pakistan (9 percent), Bangladesh (7 percent) and Guinea (6 percent) are the most common. Some 90 percent of the surveyed youth migrants were boys and young men, with higher shares of females coming from specific countries.

Economic challenges and escaping conflict and personal violence were major migration drivers. Over a third (37 percent) of respondents were unemployed and actively seeking work before departure, while another 37 percent were employed, and only 15 percent were students. Education levels varied widely, with 51 percent having no or only primary education, 45 percent having completed either lower or upper secondary, and only 4 percent having a tertiary education. On average, young women migrants had slightly higher education levels than young men. Of all migrants, 92 percent were single, though for young women, 27 percent were in a couple and 21 percent had children (compared to only 3.5 percent of males).

Agriculture, forestry and fisheries were prominent sectors of employment among young migrants before their departure, particularly in Pakistan (41 percent) and Bangladesh (34 percent). Environmental degradation, including worsening droughts, soil erosion and rising temperatures, were cited, particularly in North Africa. For example, 40 percent of young Algerians and 19 percent of young Moroccans cited slow-onset environmental changes as a key factor in their decision to migrate.

Socioeconomic opportunities, safety and family networks were key factors influencing their choice of destination, with approximately one-third of respondents indicating they had extended family members in Europe.

Source Based on information derived from IOM. 2024. DTM Europe – youth on the move, travelling by sea and by land to Europe in 2023. Grand-Saconnex, Switzerland. https://dtm.iom.int/reports/europe-youth-move-travelling-sea-and-land-europe-2023

Evidence from Demographic Health Surveys in 26 countries – primarily from sub-Saharan Africa, with some from Asia and Europe – shows that youth internal migration rates are generally high and vary significantly by country and gender (Figure 2.13).Young women (aged 15–24) are in most cases more likely than young men to have migrated within their country at least once in their life, contrary to international migration patterns. Among female youth, the incidence of internal migration ranges from 87 percent in Bangladesh to 14 percent in Armenia and Tajikistan. For male youth, the incidence ranges between 61 percent in Gabon to 4 percent in Armenia. Only three countries in the sample – Cambodia, Gabon and Mozambique – have a notably higher incidence of internal migration among male youth than female youth, while in the United Republic of Tanzania and Timor-Leste, female and male youth report migration at similar rates.

In most cases, female youth migrate internally at younger ages than male youth, with the probability of having migrated in the last five years peaking around the age of 22 for women and the age of 25 for men (see Figure 2.14).

Female youth often migrate earlier, due to marriage, as detailed further below, while young men tend to migrate later, primarily for employment, often after completing education.54 The gender gaps in migration rates are smaller among older adults in many countries, but in general women continue to have a higher probability of migrating during their life.

MOST YOUNG PEOPLE MIGRATE WITHIN THEIR OWN COUNTRIES RATHER THAN CROSSING INTERNATIONAL BORDERS.

© IFAD/ASAD ZAIDI IN SINDH, PAKISTAN, 28-YEAR-OLD GOHAR COLLECTS ROSES ON HER FARM AFTER TAKING A LOAN OF 10 000 RUPEES TO BUY GOATS AND SUPPORT HER LIVELIHOOD.

Figure 2.13

YOUNG WOMEN ARE MORE LIKELY THAN YOUNG MEN TO MIGRATE INTERNALLY

The share of individuals who have ever migrated, by sex and age group

Notes: The countries are arranged by GDP per capita in PPP. In these surveys, male and female respondents aged 15–49 were asked if they had always lived in their current place of residence. If their responses were negative, they were asked where they moved from and when, enabling an examination of migration patterns between and within rural and urban areas. Migrants are individuals who have not always lived in their current place of residence and have thus relocated at least once between their birth and the time of the interview. Therefore, these datasets identify youth migrants at the place and households of destinations, not in the household or place of origin. Ten of the surveys also inquire about reasons to migrate.

Source: Author’s calculations based on 26 national-level datasets from the Demographic Health Surveys (DHS) for selected countries with migration information.

Figure 2.14

INCIDENCE OF MIGRATION PEAKS AROUND AGE 22 FOR WOMEN AND 25 FOR MEN

Proportion of individuals who migrated in the past five years, calculated as a share of the total population by age and sex

Note: Coloured, shaded areas represent the 95-percent confidence intervals

Source: Author’s calculations based on data from the Demographic Health Surveys (DHS) for selected countries with migration information. The trend for women is based on data from 26 countries: Albania, Armenia, Bangladesh, Benin, Burundi, Burkina Faso, Cambodia, Cote d'Ivoire, Ethiopia, Gabon, Ghana, Jordan, Kenya, Madagascar, Malawi, Mozambique, Nepal, Philippines, Rwanda, Senegal, Tajikistan, United Republic of Tanzania, Timor-Leste, Uganda, Zambia and Zimbabwe. The trend for men is based on 23 of these countries; Bangladesh, Philippines and Tajikistan are excluded due to data unavailability for men.

There is significant heterogeneity in the direction of youth migration patterns across the selected countries. Around 30 percent of youth migrants engage in rural-to-rurala migration across the entire set of countries, but this type of migration is particularly important at lower levels of GDP per capita (Figure 2.15). For instance, in both Burundi and Rwanda, over 60 percent of young migrants are rural-to-rural migrants. Other studies also show that on average in low- and middle-income countries, more people migrate between rural areas than from rural to urban areas,45, 57 often in search of arable land. On average, young women are more likely than young men to migrate between rural areas.

Figure 2.15

RURAL-TO-RURAL YOUTH MIGRATION IS PROMINENT, PARTICULARLY IN COUNTRIES AT LOWER LEVELS OF ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT

The types of migration patterns, by sex and age group

Source: Author’s calculations based on data from the Demographic Health Surveys (DHS) for 26 countries with migration information. The countries are arranged by GDP per capita in PPP. Migrants are defined as those individuals who have migrated at least once between their birth and the time of the interview.

Rural-to-urban migration varies by country (Figure 2.15). In Nepal, over 60 percent of young male migrants migrate from rural to urban areas, whereas in Gabon, Ghana and Tajikistan the proportion is relatively small. Additionally, no consistent gender patterns have been identified in rural-urban migration.

Urban-to-rural migration is also notable (Figure 2.15), with movement patterns indicating circular and seasonal movements or return migration. In many cases, youth work in cities to save money before returning to begin a family and start their own farm.58 A study in Nairobi noted that 41 percent of male migrants aspired to return to their villages in the next 12 months, and 76 percent planned to return permanently.59 Young female migrants, however, were less likely to express an interest in returning permanently to their villages.59

Urban–to-urban migration is more common in higher income and highly urbanized countries, where it tends to dominate migration patterns (Figure 2.15). In Albania, for instance, migration between urban areas accounts for 62.2 percent and 42.1 percent of male and female youth migration, respectively. In Gabon, where most of the population live in urban areas, over 85 percent of migration for both male and female youth occurs between cities.60 Migration to and from urban areas may involve smaller towns rather than major cities, as towns are typically classified as “urban” in Demographic and Health Surveys. Box 2.3 offers a more detailed analysis of youth migration along the rural–urban continuum in East and West Africa.

Migration patterns among older cohorts mirror the youth cohort, reflecting the fact that many migrants relocate to their current residence before the age of 25.

© FAO/ANIS MILI IN GOUBELLAT, TUNISIA, INÈS MESSAOUDI HOLDS A ROMAN JAR FILLED WITH OIL WHILE WORKING IN AN OLIVE GROVE.

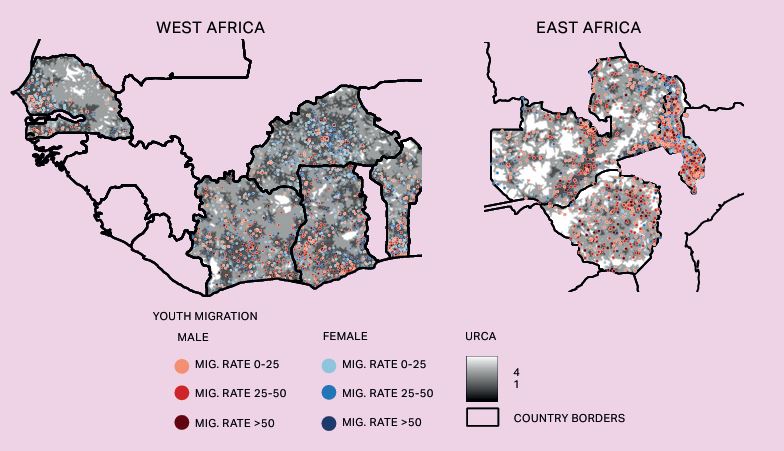

Box 2.3

SPATIAL PATTERNS OF YOUTH MIGRATION IN WEST AND EAST AFRICA

Youth migration is not limited to large cities, with many young people also migrating to peri-urban and intermediate cities. In the United Republic of Tanzania, youth often migrate to nearby secondary towns, which offer off-farm jobs and are more accessible financially than big cities, allowing easy return to their home villages if needed.i Rural–urban distinctions are commonly used in analysis, including in this report, due to limitations in geospatial data, but they mask a more nuanced understanding of youth mobility across the urban–rural continuum. Taking advantage of the availability of geo-referenced data from several Demographic Health Surveys, the variation in youth migration rates is examined across space and by gender. Rural youth migration rates, calculated at the survey cluster and focused on youth who have migrated in the five years preceding the survey, are overlayed on the urban-rural catchment areas (URCA) mapsii, iii (Figure A). Youth migration rates are measured at destination.

Urban and peri-urban areas attract a large share of migrants. Female youth migrate to both urban and rural areas.iv, v In contrast, male youth migration is largely towards urban centres vi, particularly peri-urban areas. These gendered patterns are more pronounced in countries in West Africa than in East Africa. The spatial mobility patterns reinforce the findings that female and male youth migration are frequently motivated by different factors.vii–ix

FIGURE A. YOUTH MIGRATION RATES BY GENDER ACROSS THE URCA SPACE

Notes: Refer to the disclaimer on page ii for the names and boundaries used in this map. Urban and peri-urban areas are marked in darker shades of grey on the maps. Categories for DHS clusters are: “Mig. Rate 0–25” for cluster with migration rate above 0 and below 26 percent, “Mig. Rate 26–50” for clusters with migration rate equal or greater than 26 percent and below or equal to 50 percent, and “Mig. Rate >50” for clusters with a migration rate above 50 percent. Clusters with no migration (i.e. the migration rate is 0) are excluded from the analysis.

Source: Author's own elaboration based on data from the Demographic Health Surveys (DHS) for selected countries.

Notes: Refer to the Notes section for full citations.

The spatial distribution of youth migration is also explored across opportunity spaces (see Appendix 1). Figure B shows the distribution in each country of the shares of male and female youth migrants according to the type of space in which they live.

Larger shares of young migrants live in areas with higher opportunities. These are areas with higher market connectedness and agricultural potential, thus offering enhanced opportunities in terms or employment, education, agripreneurship and access to markets (marked in blue). Across all countries but Burkina Faso and Senegal, clusters with more than 50 percent of young migrant display larger shares of rural young migrant living in areas characterized by both high agricultural and market opportunities, which could signal the fact that youth moved seeking better livelihood options. In most countries, large shares of young migrants live in areas with strong agricultural opportunities (either with strong or moderate market opportunities, marked in green). This is not surprising, given that all countries but Zimbabwe, in the sample have traditional agrifood systems, with higher reliance on the agriculture sector, and where rural-to-rural migration is prevalent (see Figure 2.15). Senegal stands out as an exception, where youth migration is directed toward areas with strong market opportunities but lower agricultural potential (purple), as well as areas with moderate opportunities (orange). This likely reflects youth engagement in urban informal off-farm agrifood system roles, such as street vending.

FIGURE B. YOUTH MIGRATION RATES BY GENDER ACROSS OPPORTUNITY SPACES

Notes: Categories for DHS clusters are: “Mig. Rate 0–25” for cluster with migration rate above 0 and below 26 percent, “Mig. Rate 26–50” for clusters with migration rate equal or greater than 26 percent and below or equal to 50 percent, and “Mig. Rate >50” for clusters with a migration rate above 50 percent. Clusters with no migration (i.e. the migration rate is 0) are excluded from the analysis..

Source: Author's own elaboration based on data from the Demographic Health Surveys (DHS) for selected countries.

Notes: Refer to the Notes section for full citations.

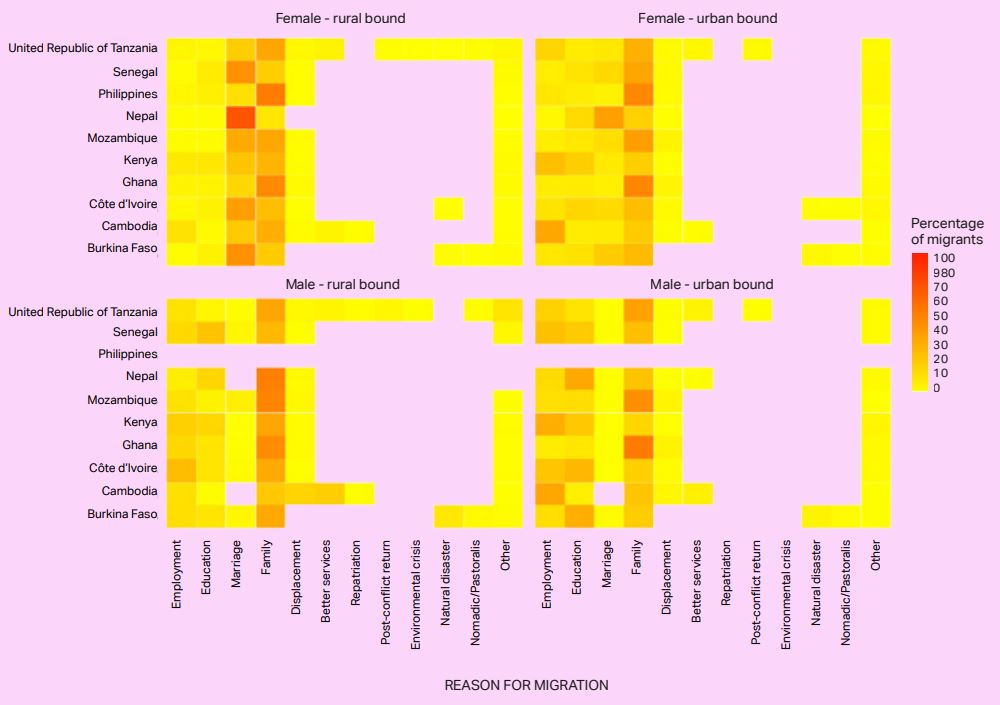

KEY DRIVERS OF YOUTH MIGRATION

Youth migration is driven by a complex and often intertwined array of factors at the individual, family, community, national and international level.61 For many youth, migration is often a family strategy to diversify income and improve household welfare,62 especially in contexts where state-provided welfare systems are absent or weak. In such cases, the decision to migrate is not made in isolation, and parents and elders may support youth migrants financially, with the expectation of future remittances.63 When migration is a family strategy, it implies for youth balancing personal aspirations with familial obligations and expectations.

Youth migrate internally for various reasons, but primarily for marriage, education, employment and to join family members (Figure 2.16). Both young women and men often cite joining other family members as a primary reason for migration to both rural and urban areas. For young women, marriage and family reunification are the predominant reasons, especially for those migrating to rural areas. In Nepal, marriage accounts for nearly all female youth migration to both urban and rural areas, while in Cambodia and Kenya, employment is a leading driver of young women’s migration to cities. For young men, education and employment are the primary drivers especially for rural to urban migration (Figure 2.16), reflecting the concentration of secondary schools in urban areas and the poorer quality of schools in rural areas.64,65 When youth migrate primarily for work or education, the process is rarely a single event and instead often involves a series of moves.19,66,67 Youth may migrate for short or long periods, return home, stay temporarily and then migrate again. However, quantitative data capturing these multiple migration moves remain limited (see Box 2.4). These findings corroborate evidence68, 69 showing that youth migration – particularly internal migration – is driven by reasons beyond immediate economic gains. Migration age profiles are strongly correlated with the age structure of life-course transitions such as education, entry into workforce and marriage, especially among women.70 These transitions differ widely both within and across societies and are further shaped by social markers of differentiation including gender, class and Indigenous or ethnic identity.

The different motivations for internal migration have distinct implications for the relations between migrants and their families and communities of origin, as well as for the welfare and opportunities of young people. Youth migrating for education often require financial support instead of remitting money back home.65 Even when migration is undertaken for employment, families often cover the initial costs,71 and some migrants may stay with extended family members or close friends as they transition into the new life at their destination.65, 66, 72, 73 In fact, youth migrants often remit less than migrants over 25 years old, in part because they need time to integrate into the host labour markets and begin earning higher wages.74 Studies show that young people migrating for education often come from the wealthiest households, while those migrating for work have on average access to financial resources at a level similar to the rest of the population.65

MIGRATION PATTERNS DIFFER BY GENDER. YOUNG WOMEN OFTEN MIGRATE FOR MARRIAGE OR FAMILY, YOUNG MEN FOR JOBS.

The nature of structural transformation and agrifood systems transition in a given context influences youth migration patterns. Urbanization, youth population growth, the local availability of off-farm work, and access to land and other productive assets all shape youth decisions to migrate. A study in Nigeria41 found that urbanization encourages youth migration, though the propensity to migrate differs depending on gender, education and ownership of assets. In general, women and better-educated youth are more likely to migrate to cities, while youth in households with livestock are less likely to do so. Owning land and physical assets is positively correlated with temporary migration, while larger landholdings deter permanent migration.41 Other studies also point to access to land as an important determinant of youth migration. Larger than expected land inheritance significantly reduces the probability of both long-distance permanent migration and migration to urban areas in Ethiopia, particularly among male youth.42

YOUTH MIGRATION IS CLOSELY LINKED WITH LIFE TRANSITIONS LIKE WORK, EDUCATION AND MARRIAGE.

For many young people, internal migration is often also a response to a lack of decent employment opportunities in rural areas. The prospect of better jobs, even within the informal economy, draws young people to cities.75 Data from school-to-work transition surveys also highlight job satisfaction as a key motivation for migration, with strongly dissatisfied working rural youth more than twice as likely to migrate as those who were satisfied with their jobs.76 However, a study in Zambia77 examining the role of rural vibrancy in youth migration decisions found that youth aged 15–24 were less influenced by local economic opportunities, including the availability of non-farm economic opportunities, than older individuals. While areas with greater agricultural productivity were associated with reduced rural out-migration, increased local non-farm economic activity seemed to have the opposite effect, increasing rural out-migration. However, these patterns are not observed among youth.77

International migration, however, is more likely to be driven by economic reasons than internal migration. Unemployment and underemployment are strongly associated with intentions to migrate abroad, as shown in Figure 2.17, which illustrates key factors correlated with international migration plans among youth and adults. Youth planning to migrate internationally also tend to be better educated and are less likely to be female, married or living in rural areas (Figure 2.17).78, 79 In Lebanon, youth from poorer backgrounds have a higher propensity to migrate, with unemployment and higher education levels increasing the likelihood.80 In the European Union as well, youth with higher levels of education and those who are unemployed, particularly in countries with high youthto-adult unemployment ratios, are more likely to have intentions to migrate.79 Additionally, among youth who have migrated in the last five years, the likelihood of planning another move is higher, especially when experiencing dissatisfaction with living conditions in the local area.

Food insecurity also influences youth migration plans (Figure 2.17). Youth living in areas experiencing moderate food insecurity have a significantly higher probability of making plans to migrate abroad. According to figure 2.17, it is significant. Youth facing severe food insecurity may be trapped in situations of vulnerability

Migration patterns among older cohorts mirror the youth cohort, reflecting the fact that many migrants relocate to their current residence before the age of 25.

© FAO/JEAN BAPTISTE NKURUNZIZA IN RWANDA, A YOUNG FARMER PROUDLY HOLDS A CHICKEN RAISED ON A MODEL POULTRY FARM, PART OF A GROWING MOVEMENT EMPOWERING YOUTH WITH SKILLS AND INCOME THROUGH SUSTAINABLE EGG PRODUCTION.

Figure 2.17

MODERATE-TO-SEVERE FOOD INSECURITY INCREASES YOUTH'S PLANS TO MIGRATE INTERNATIONALLY, WHILE SEVERE FOOD INSECURITY HAS NO SIGNIFICANT EFFECT

Notes: The dependent variable is a binary indicator equal to 1 if the respondent intends to migrate within the next 12 months. The estimates are taken from a linear probability model with country fixed effects. The variables moderate food insecurity and severe food insecurity are measured at the sub-regional level. The variable underemployment is an indicator equal to 1 if the respondent is either unemployed or underemployed.

Source: Author’s own elaboration based on individual-level survey data from the Gallup World Poll for 2015 for 131 countries.

YOUTH MIGRATION AND LABOUR SHORTAGES IN AGRIFOOD SYSTEMS

Youth migration can enhance livelihoods and incomes, while addressing labour shortages in agrifood systems. If well-managed, youth migration could fill critical labour gaps within agrifood value chains3, 5 and revitalize rural areas in countries facing shrinking youth populations.

Global agrifood systems already rely heavily on both internal and international migrants. The COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated this dependence, as border closures and mobility restrictions led to severe labour shortages in many agricultural supply chains, especially those reliant on seasonal labour, with disruptions in production as well as the processing and distribution of food.81 Temporary and seasonal migration – both within and across borders – is a longstanding characteristic of rural livelihoods, linked to seasonality of agriculture and household income diversification strategies (see Box 2.4). For instance, major agricultural exporters such as Brazil,82 Chile83 and Mexico84 depend on internal migrants, often from Indigenous communities, to fulfil seasonal labour needs on commercial farms. In South Asia, internal migrants form a substantial portion of the workforce in aquaculture and fish processing industries in countries like Bangladesh and India.85, 86

For countries in the early or intermediate stages of agrifood system transition but with large youth populations, such as protracted crisis, traditional and expanding agrifood systems, migration can enhance youth economic prospects. Evidence from Peru demonstrates that temporary labour migration, whether to work within or outside agrifood systems, significantly improves the welfare of young migrants.87 Temporary labour migration is a function of agricultural activities with different crop cycles, ensuring continuous employment throughout the year. While agriculture remains a key employer for youth migrating to rural areas, migration enables access to non-agricultural opportunities, particularly for youth moving to urban areas. A study in Ethiopia, Malawi, the United Republic of Tanzania and Uganda found that youth migration to urban areas facilitates entry into non-agricultural labour markets, whereas rural-to-rural migration primarily supports livelihood diversification within the agrifood sector.88 This highlights how migration – whether to rural or urban areas – can help young people supplement their incomes and reduce dependence on a single economic activity, making them more resilient to economic and environmental shocks.

Migration also affects the agricultural activities and income of those who stay in the household. Studies in Ethiopia and Malawi demonstrated that youth migration affects rural households’ labour allocation and decisions, with the labour endowment of migrants replaced by other members of the households or leading to an increase in hired labour.2 The impact on household income varies by context; in Malawi, youth migration has been linked to reduced total household income, whereas in Ethiopia, it has led to higher net income.

In industrial agrifood systems, international migration is increasingly vital for addressing agricultural labour shortages caused by declining rural populations. Australia, Canada and the United States of America have long relied on migrant workers to sustain their agrifood industries.89, 90 Similarly, Southern European nations like Greece, Italy and Spain are experiencing a growing dependence on migrant labour as local populations move away from agricultural work.91 In Greece, for example, migrants now constitute a substantial share of the workforce in sheep, cattle and goat husbandry, reflecting broader trends in workforce restructuring.92, 93

Although youth constitute a large proportion of migrant agricultural workers, comprehensive statistics on their exact numbers remain scarce due to data aggregation practices. Migrant youth under 18 are often categorized alongside children in child labour studies, obscuring their specific contributions. Research indicates that youth under 18 can comprise 10 percent to 40 percent of migrant agricultural workers and 16 percent to 80 percent of child labour in specific agrifood value chains.94 However, they often face precarious working conditions, including lower wages, longer working hours, reduced educational opportunities and higher occupational hazards compared to local youth.95

Box 2.4

YOUTH TEMPORARY AND SEASONAL MIGRATION

Seasonal migration is a temporary form of migration in which individuals or entire families move during specific periods of the year, returning home afterwards. This movement can occur within national borders or across countries and is influenced primarily by agricultural calendars. In Senegal, mobile phone data tracking confirms spikes in seasonal rural-to-rural migration during agricultural harvest period.i Recent studies reveal trends of seasonal migration of young people during the rainy season, suggesting diverse income diversification strategies.ii, iii Seasonal migration tends to be more accessible for landless, low-income and marginalized groups, as well as youth, due to its lower skills requirement and fewer upfront financial costs.iv, v A study from India showed that individuals aged 16–40, particularly from scheduled tribes and castes, are overrepresented in short-term migration flows.vi In Benin, many young people from the Barienou district migrate annually to Nigeria to work in agriculture. Nearly half of migrants interviewed are aged between 18–27 years old, with primary-educated and married youth more engaged in farming activities.vii In Brazil, young men aged 17–30 years from rural areas with low-education and farming backgrounds are the predominant seasonal migrant workers in sugarcane mills.viii Similarly, in the Valle de Uco in Argentina, seasonal migrant workers are mostly young men aged 20–30.ixYouth also represent a large share of seasonal international migrant workers supporting agriculture, particularly in fruit and vegetable production within industrial agrifood systems.x

Seasonal migration presents both opportunities and challenges for youth. Seasonal migration to nearby areas allows youth, especially male youth, to return home for the farming season.ix This supports continued ties with family land while awaiting inheritance (see Chapter 3). Some youth also use seasonal migration to accumulate capital for future agricultural investments. xii However, seasonal migration can negatively impact youth health, social life and working conditions.vii For example, young men migrating to work on farms in Nigeria are often recruited by intermediaries and employed under precarious working conditions.xiii Likewise, in Ethiopia, many young people migrate to urban centres to work as daily labourers, particularly after the harvest season. Additionally, while seasonal migration serves as a vital coping mechanism for food insecure households or a supplemental livelihood strategy, it can also reduce agricultural yields due to labour shortages in sending areas, increase school dropouts and deepen social isolation.xiv Seasonal migration, whether undertaken by individual youth alone or alongside other adult family members, as seen in cotton harvesting in Pakistanxv, can restrict access to education and healthcare, increase risks of child labour and ultimately undermine long-term human capital developmentxvi(see also Chapter 3, Box 3.2).

Temporary and seasonal migration also have gender patterns. In Benin, girls as young as 13 years migrate temporarily, with some seeking independence and/or escaping forced marriages. Many end up working in processing, street food or as domestic servants.xiii In Mali, temporary migration is increasing, particularly among unmarried girls in search of autonomy. xvii Similarly, in Tunisia, seasonal migration patterns have shifted over time, with rural young women increasingly engaged in short-term migration to work in textile factories, domestic labour or agriculture.xviii

When managed effectively, temporary and seasonal migration can be a “triple-win” – it can support migrants’ livelihoods, alleviate labour shortages at destination areas, and contribute to economic development in origin communities through remittances and skill transfers. Bilateral labour migration agreements, seasonal agricultural migration schemes and entry quotas are some of the policy tools used to regulate this form of migration (see Chapter 7).

Despite its importance, seasonal migration remains poorly understood due to limited and inconsistent data.

Many seasonal migration movements go unrecorded due to the lack of standardized definitions and the short-term nature of these movements. Data are rarely disaggregated by age, making it difficult to analyse youth-specific trends. While Eurostat provides comparable seasonal migration data for European countries, similar initiatives are lacking in many other regions. Improved data collection is crucial for assessing the scale, trends and impacts of seasonal migration on migrants and agrifood systems.

Notes: Refer to the Notes section for full citations.