OPPORTUNITIES

MOVE FOOD

FORWARD

© FAO/RUSSELL WAI IN PAPUA NEW GUINEA, GIBSON AND GENO GABI STAND IN THEIR PLANTATION OF SWEET POTATOES.

03 Access to assets and resources

© FAO/TANG CHHIN SOTHY – IN KAMPONG CHHNANG, CAMBODIA, CHHUM KIMSEAK, AGED 17, RIDES HER MOTORBIKE TO SCHOOL.

© FAO/RUSSELL WAI IN PAPUA NEW GUINEA, GIBSON AND GENO GABI STAND IN THEIR PLANTATION OF SWEET POTATOES.

KEY MESSAGES

- Rural youth, and especially young rural women, lag behind their urban counterparts in terms of social capital and formal and informal participation in policy and decision-making processes related to agrifood systems.

- Rural youth face significant disadvantages in accessing quality education and training opportunities, impacting their opportunities to secure decent work in agrifood systems. 74 percent of rural young people complete lower secondary education, compared with 85 percent of urban young people. These challenges are more severe in protracted crisis and traditional agrifood systems, both for young rural women and migrants.

- Fewer than half of young people own any land due to barriers such as delayed inheritance and rising land prices. These constraints, and others like limited access to capital, hinder young people, especially young women, who want to farm from accessing land and establishing independent livelihoods.

- There are significant gaps in the data and evidence regarding youth access to natural resources – such as forestry and fisheries – and assets like livestock. Case studies suggest that young people encounter challenges in accessing more valuable and capital-intensive livestock, such as dairy-producing animals, with the limited available data suggesting that youth and youthled households have smaller livestock holdings than adults or households led by adults.

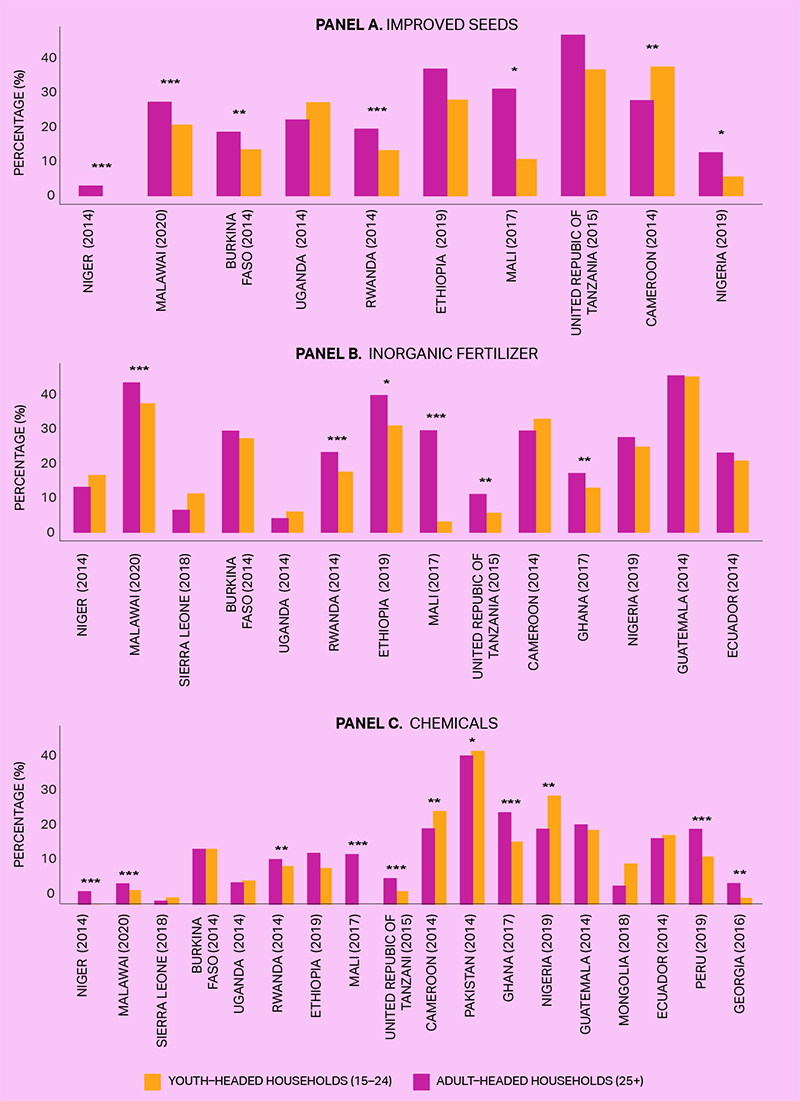

- Young people’s inadequate access to inputs, machinery and technology reduces the propensity of youth to work in agrifood systems. Data from selected countries suggest that adultheaded households, as compared to those led by youth, enjoy greater uptake of and access to improved seeds, fertilizers and chemicals in the majority of countries.

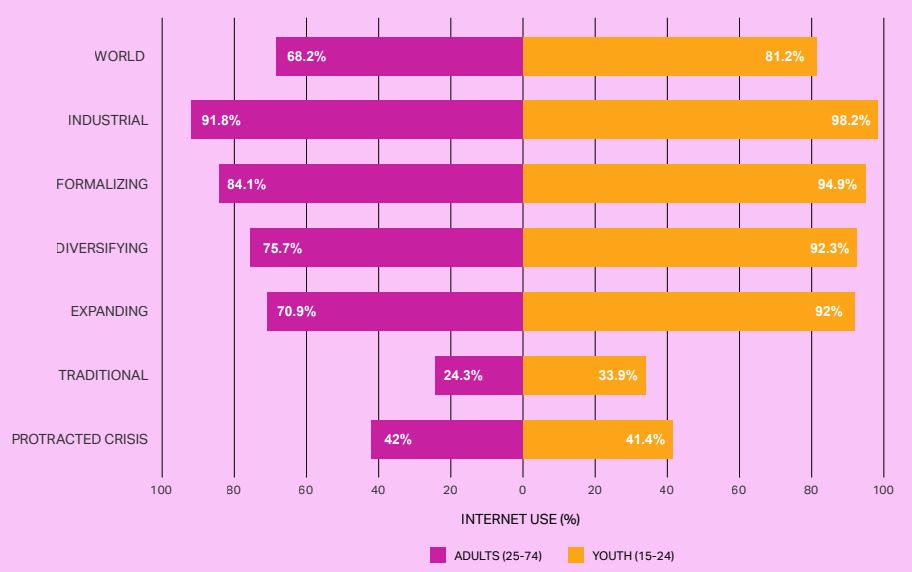

- Youth are more digitally connected than adults, but disparities persist. 81.2 percent of youth use the internet, compared to 68.2 percent of adults, reflective of higher digital engagement among young people. However, digital access varies widely by agrifood system: 98.2 percent of youth use the internet in industrial agrifood systems, but only 33.9 percent in traditional agrifood systems. The digital gap between youth and adults decreases as agrifood systems transition from traditional to industrial, but youth in protracted crisis settings remain the most digitally excluded.

INTRODUCTION

Greater access to assets and resources is essential for the empowerment of young people, their economic independence and productive participation in agrifood systems. However, young people frequently face significant challenges in accessing resources due to generational and gendered power dynamics, as well as structural, economic, social and spatial constraints.1 Policy and legal barriers may also impede access. Delayed access to farmland and other resources (e.g. fisheries or forestry rights) through inheritance means that many young people establish themselves as independent farmers only once they are no longer officially classified as youth, although their involvement in farming might have started earlier. For many young women, farming becomes a vocation only after marriage, and even then, they may not have independent access to land.2

There is a growing interest in understanding what motivates young people to pursue agrifood system livelihoods. Studies have sought to ascertain the role of different assets and resources in facilitating young peoples’ access to livelihoods in agrifood systems, including whether access to knowledge and technology can offset negative perceptions of work in agriculture or agrifood system value chains. The reality is much more nuanced and suggests that decisions may also be driven by the presence of concrete opportunities, such as access to land or wage employment.

The literature on generational renewal of farming identifies different ways in which young people can enter farming: as newcomers to the agricultural sector, by moving directly from working on family farms to becoming independent farmers, or by returning after a period of time away for education or for work. For example, in rice-growing villages in Central Java, West Java and South Sulawesi, Indonesia, landlessness is widespread and less than half of farmers own the land they cultivate. Young people from smallholder families may inherit a small piece of land one day, likely when they are no longer young, while youth from landless and landpoor families opt for temporary migration or wage labour and sharecropping.3

Evidence also shows that the likelihood of embracing innovation is related less to age than to being a newcomer to the agricultural sector, which undermines the idea of technology and innovation as a silver bullet to motivate young people to remain in agriculture.4 Intergenerational relations and interdependencies, including inheritance and the transfer of knowledge, can facilitate or hamper the generational renewal of agricultural labour, a process further complicated by the intersection with education, marriage and family formation.2

Contextual factors including social norms and policy environment also shape access to assets and resources. Young people continually renegotiate their position in society as well as in relation to assets, especially land. Within agrarian structures, young people exercise constrained agency, meaning they navigate, adapt to and sometimes challenge the limitations imposed by generational and gendered hierarchies. This concept acknowledges that while young people – especially young women – face structural barriers to accessing resources and decision-making power, they also find ways to negotiate space for autonomy within these constraints.

Following the conceptual framework outlined in Chapter 1, this chapter examines young people’s access to the assets and resources that underpin agrifood systems livelihoods, highlighting the unique barriers they encounter due to their social position. Five broad categories of assets and resources are considered: social capital; human capital with a focus on education, training and skills; natural capital (land, livestock, forest and fisheries resources); financial capital; and physical capital, including digital access, inputs and different types of technology and tools relevant for agrifood systems. All of these categories contribute to boosting young people’s agency, defined as the ability to determine one’s goals and act upon them, as discussed in Chapter 1. 5

SOCIAL CAPITAL

Social capital refers to the networks, relationships and trust that connect people and help them work together to achieve common goals. These connections can open doors to resources, information and opportunities that young people need to succeed. It plays an important role in shaping how young people engage with and influence agrifood systems.6 Social capital is a key component of building strong, sustainable rural communities.7, 8 When combined with other factors, like good infrastructure and supportive institutions, social capital can help rural economies thrive.9 At its core, social capital is about relationships – how they are formed, how they change and how they help communities adapt over time.10

There are two main types of social capital. Bonding social capital refers to strong connections within close groups, like family and friends. These ties create a sense of loyalty and trust, which helps people support one another.10 Bridging social capital, on the other hand, connects people from different backgrounds or communities. This kind of social capital helps young people access new ideas, opportunities and resources beyond their immediate circle.11

In rural areas, both bonding and bridging social capital play an important role. Young people often rely on close networks of family and friends for emotional and practical support. At the same time, having connections outside of these circles – through schools, community organizations or agricultural cooperatives – can help them find new opportunities. For instance, a study of young farmers in Northern Greece revealed that social capital was generally low, with limited participation in voluntary organizations and low trust in institutions. This hindered their ability to engage in collective activities and access new resources. However, those with stronger trust in personal relationships, such as family and friends, were more likely to participate in collective efforts, highlighting the role of personal networks in compensating for weak institutional support.12

The relationship between agency – as defined in Chapter 1 – and social capital is dynamic. While networks play a key role in building social capital,13 agency is essential to effectively mobilize and utilize this social capital.14 Conversely, when social capital is weak – due to limited trust or poor institutional support – it can constrain youth agency, limiting their ability to participate meaningfully in agrifood systems. Youth who lack formal access to resources, such as land or credit, often rely on social capital to bridge these gaps, drawing on family ties, peer networks and community connections.

YOUTH WHO LACK FORMAL ACCESS TO RESOURCES, SUCH AS LAND OR CREDIT, OFTEN RELY ON SOCIAL CAPITAL TO BRIDGE THESE GAPS.

Collective action is an important means for youth to act as agents of change. Many young people are active participants in cooperatives, social movements and associations, to varying degrees across countries and typologies of agrifood systems.16 Such collective processes can amplify the voice of young people as agents of change for agrifood systems transformation. Social capital focused on building relationships with peers and friends is particularly beneficial for youth when participating in associations and organizations, because they can acquire expertise and demonstrate the capacity to organize.17 Case studies in settings as diverse as Canada, the Russian Federation and Thailand demonstrate that joining collective organizations can facilitate youth’s access to natural resources, finance and markets,16 whereas evidence from Uganda suggests that being part of rural organizations has helped young people overcome psychological, physical and economic barriers to improved rural livelihoods.17

YOUTH OFTEN EXERT LITTLE INFLUENCE ON DECISION-MAKING IN GLOBAL FORUMS, INCLUDING ON AGRIFOOD SYSTEMS AND CLIMATE, DUE TO A LACK OF PARTICIPATION AND VOICE.

Nonetheless, youth participation in collective action faces challenges. Young people have lower levels of experience and resources and may therefore experience greater difficulties in establishing, leading and holding rural organizations to account.18-19 As suggested by Trivelli and Morel, living in a remote rural setting constitutes the first level in a “hierarchy of exclusion” which can intersect with numerous other characteristics of youth. Gender is considered a major exclusion factor that interacts with rurality reducing young women’s opportunities for participation due to mobility constraints, lower literacy rates, persistent gender inequalities in the rural household and discriminatory social norms.20 Rural youth in employment or education seem to be more likely to be politically or socially engaged than economically inactive youth.21 Additionally, youth civic engagement is increasingly tied to the digital sphere, with the internet and social media expanding and redefining traditional civic spaces and forms of engagement, though lack of access to technology and digital literacy represent constraints for unconnected youth in remote rural settings.

Finally, youth often exert little influence on decisionmaking in global forums, including on agrifood systems and climate, due to a lack of participation and voice.22 Research on the lived experiences of young participants in multilateral forums notes persistent barriers to meaningful youth engagement, including inadequate support for quality participation (e.g. lack of clarity regarding objectives, pre-participation training, financial and logistical support) and insufficient inclusivity and representation. Young delegates report tokenism and feeling exploited, and most are unable to attribute any social or policy impact to their participation in global forums.23 Strategies and policies on youth are often written based on the request of donors or other development partners, rather than grassroots demand (see also Box 3.1).24

HUMAN CAPITAL

EDUCATION, TRAINING AND SKILLS

Education – including informal ways of acquiring knowledge and competencies – and training are essential for empowering youth to participate in a meaningful manner in agrifood systems, while also enabling them to strengthen their livelihoods. Without adequate skills and education, young people are more likely to be confined to low-quality jobs, perpetuating intergenerational cycles of poverty and inequality. Education is highly correlated with better wages and employment opportunities, both within and outside agrifood systems. In agriculture, education is significantly correlated with the adoption of improved technologies such as improved varieties, chemical inputs and mechanization, though the association with improved natural resource management innovations is more ambiguous.25 Agricultural extension is most effective in areas with higher education levels, highlighting the complementarities between education and agricultural extension.25

©FAO/FANJAN COMBRINK IN CHEREPONI, NORTH-EAST REGION, GHANA, CHRISTABEL KWASI AND FELLOW YOUNG WOMEN FARMERS INSPECT A FONIO PROCESSING MACHINE THAT EFFICIENTLY SEPARATES THE CHAFF FROM THE GRAIN, EXEMPLIFYING YOUTH-LED INNOVATION IN LOCAL AGRIFOOD SYSTEMS.

Box 3.1

YOUTH REPRESENTATION IN FORMAL POLITICAL PROCESSES

Youth are under-represented in formal political processes. Only 2.8 percent of parliamentarians worldwide are under 30, about one-third of whom are young women. The share of youth in single and lower chambers is 3.2 percent globally but is lower in Africa and Asia at 2.3 percent and 1.8 percent, respectively.i A combination of legal barriers (e.g. age and financial requirements for public office) and social norms undermines the active participation of young people, especially young women, in formal governance structures. For instance, African youth (aged 18–35) are less likely than older citizens to engage in change-making activities such as voting in elections, attending a community meeting or joining others to raise an issue, and are more likely to view government institutions and leaders as corrupt.ii

Mechanisms such as youth parliaments or national and local youth councils risk reinforcing social inequality by failing to achieve diversity and inclusion among their young constituents, particularly of the hard-to-reach majority. iii, v Such participation mechanisms tend to involve more educated, organized youth activists – high-performing and outspoken urban “elites” who do not necessarily represent the interests or share the experiences of their less educated or less socially engaged peers.iv Institutional participatory spaces dedicated to rural youth exist in a few countries, supported by the Ministry of Agriculture or local authorities. For instance, Chile’s Mesa Nacional de Jóvenes Rurales is a consultative mechanism composed of 16 youth representing different local chapters, which in turn comprise hundreds of rural young people. This platform plays a role as a sounding board for national policies and programmes targeting young smallholder farmers and youth in rural areas, such as the national Rural Youth Policy.

Analysis of rural youth civic engagement and its determinants is minimal, particularly for low- and middle-income countries. iii, v Such However, young people in rural areas seem to be less likely to participate in political activity than their urban peers,vii, ix both offline and online.x In rural communities, traditional decision-making spaces are often dominated by older generations, and even when youth are included, they frequently lack the confidence, skills and resources necessary to effectively influence decision-making outcomes. Generational power dynamics create further resistance, with elders or community leaders reluctant to share authority. Institutional and local political systems often fail to provide inclusive platforms for youth participation, while economic pressures such as unemployment force many young people to focus on immediate survival rather than civic engagement. In some regions, political instability, violence and restrictive environments also make participation unsafe, further deterring youth from engaging in community processes.xi

Notes: Refer to the Notes section for full citations.

FORMAL EDUCATION

Despite significant improvements in education globally over the last several decades, rural youth continue to be disadvantaged in access to formal education compared with their urban peers. These disadvantages start with primary and lower secondary education, which are the foundational blocks for engaging in more advanced learning and better-paid work. Averaging across all types of agrifood systems, 74 percent of rural youth complete lower secondary education compared with 85 percent of their urban counterparts. Only 20.5 percent of rural girls in protracted crisis agrifood systems complete lower secondary education, compared with over 50 percent of their male and female peers in urban areas, and with 98 percent of girls in industrial agrifood systems. In Central African Republic, Chad, Liberia, Mali and the Niger, less than 10 percent of rural girls complete lower secondary education (Figure 3.1).

ONLY 20.5 PERCENT OF RURAL GIRLS IN PROTRACTED CRISIS AGRIFOOD SYSTEMS COMPLETE LOWER SECONDARY EDUCATION.

Figure 3.1

RURAL YOUTH ARE LESS LIKELY TO COMPLETE LOWER SECONDARY EDUCATION THAN URBAN YOUTH IN TRADITIONAL AND PROTRACTED CRISIS AGRIFOOD SYSTEMS

Completion rate (%) of lower secondary school for men and women in rural and urban areas, by agrifood system typology

Source: Author's own elaboration based on data reported for SDG indicator 4.1.2 (Completion rate, lower secondary by sex and location) for 112 countries. The data – restricted to the latest available years – were downloaded from http://data.uis.unesco.org/index.aspx?queryid=3697 (28 November 2024). Three additional countries reported data on SDG 4.1.2, but an agrifood system classification is not available for these countries.

Figure 3.2

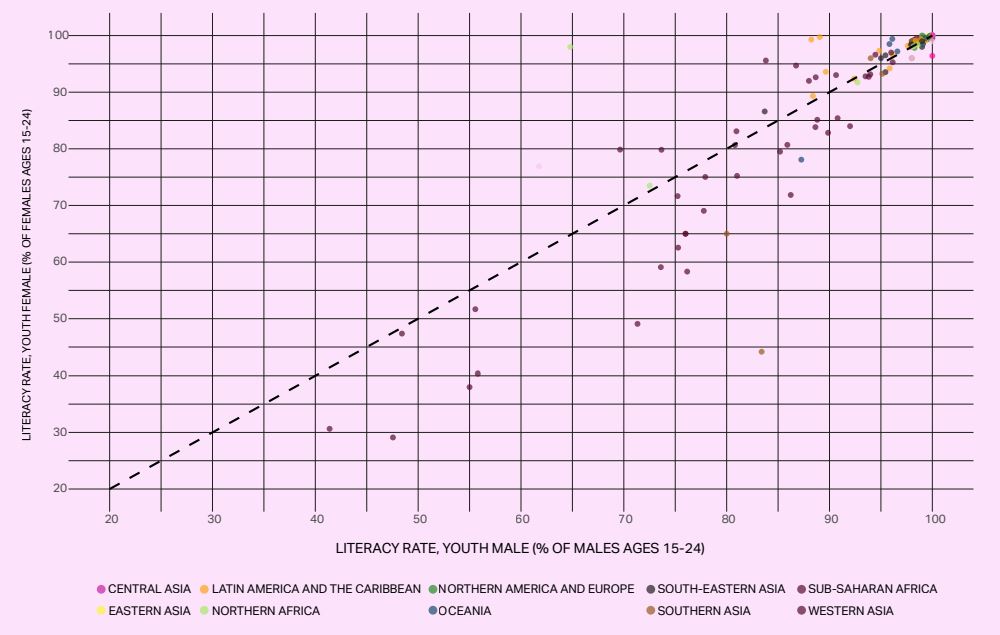

LOW YOUTH LITERACY RATES AND LARGE GENDER GAPS ARE OBSERVED IN MANY SUB-SAHARAN AFRICAN COUNTRIES

Literacy rates (%), young men vs young women, aged 15–24, by region

Source: Author's own elaboration using data from UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS). UIS. Stat Bulk Data Download Service. Processed by World Bank Gender Data Portal, https://genderdata.worldbank.org/en/indicators accessed 11 March 2025. The most recent year available can vary from 2015 (e.g. Nicaragua) to 2023 (e.g. Azerbaijan).

While marked rural–urban gaps in education are also evident in the case of traditional food systems, the gap in lower secondary education is smaller in expanding and diversifying agrifood systems, though some exceptions are visible, notably in Djibouti, the Gambia, Honduras and Iraq. In diversifying food systems, rural girls not only outpace boys in completing lower secondary education, they also reach almost the same level as urban girls. Rural–urban and gender gaps disappear in industrial agrifood systems. Young migrants also face challenges in accessing education (see Box 3.2).

LITERACY AND NUMERACY SKILLS OFTEN REMAIN ALARMINGLY LOW EVEN AMONG THOSE WHO ATTEND SCHOOL.

Between 2000 and 2022, the youth literacy rate increased from 87 percent to 93 percent, globally.26 However, literacy and numeracy skills often remain alarmingly low even among those who attend school. Low literacy and numeracy have been identified as binding constraints on competitiveness across sub-Saharan Africa, leading to low-quality jobs and persistent poverty and inequality.27 Among young men and women aged 15–24 in subSaharan Africa, 21.4 percent lack basic literacy skills,26 with literacy skills also low in several countries in South Asia and North Africa (Figure 3.2).

© FAO/ALISA SUWANRUMPHA IN NORTHEASTERN THAILAND, NOOPHEEN MEKAWAN, MARKETING SECRETARY OF THE BAAN HUAI BONG FISH PROCESSING GROUP, SHARES HER STORY DURING AN INTERVIEW AT THEIR ‘ONE’ BRAND SHOP IN NONG BUA LAM PHU.

Box 3.2

EDUCATION AND TRAINING OF YOUNG MIGRANTS, REFUGEES AND INTERNALLY DISPLACED PERSONS (IDPS)

Internal and international youth migrants face a number of specific barriers to education and training. Residence requirements, a need for documentation (or even perceived need) or the threat of deportation can keep children and youth from enrolling in school. Young seasonal migrants and/or the children of seasonal migrant workers may also face additional barriers including incompatibility of school calendars, admission timing, the expectation that they will work with their families, and the location of agricultural work in remote areas where schools may not be present or transportation unavailable.

Despite the challenges, migration to towns, cities or abroad can increase access to education compared to availability in the area of origin. Many youth migrate from rural to urban areas for secondary or tertiary education. In OECD countries, immigrant youth often achieve better educational outcomes compared to peers who remained in their country of origin.i However, their outcomes tend to lag behind those of native-born peers, with the gaps shrinking for the second generationi and largely disappearing by the third.ii The age of migration can also affect education outcomes: for example, among Mexican immigrants to the United States of America, those who arrived between the ages of 0 and 6 years have an educational advantage compared to their peers who do not migrate and those that migrate in the later years of childhood.iii

Children and youth left behind in migrant-sending households

Migration from rural areas can also positively or negatively impact the education of children and youth who are left behind. Receiving remittances from migrant household members can pay for school fees and related costs and help their households respond to shocks, allowing them to continue their education. A study using data from 122 developing countries from 1990 to 2015 found that remittances had a positive effect on school enrolment and completion rates, and that investment in girls’ education increased more than in boys’.iv Conversely, children/youth may withdraw from school (or be pulled out) to compensate for the labour of relative(s) who have migrated. Such youth experience increased risks of mental health concerns including depression and anxiety, and worse nutritional outcomes compared with the children of non-migrants.v, vi

Young refugees and IDPs

Displacement poses serious challenges for the education of young people. An estimated 40 percent of the forcibly displaced population are under 18, totalling 47 million children.vii Nearly half of school-aged refugees are out of school, with persistent gender disparities.vi Some 66 percent of refugees are in protracted situations; low- and middle-income countries host 71 percent of the refugee population, globally, with least developed countries (LDCs) accounting for 22 percent.vii Displacement can cause large influxes of children and youth in a short period of time, necessitating urgent action and the allocation of considerable resources. In remote and rural areas, key challenges include the need for parallel systems to educate displaced students, a lack of recognition of previous degrees or courses, teacher shortages, slow recruitment processes, language barriers, trauma, insufficient psychosocial support, teachers without adequate training to deal with displaced populations, social tensions, and prolonged detention or transit zones without access to education while applications are processed.viii

Notes: Refer to the Notes section for full citations.

At the global level, the gender gap in literacy stood at 2 percentage points in favour of men, but is significantly larger in many countries in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia.28 For example, in Pakistan 65 percent of young women were literate in 2019 compared with 80 percent of young men, while in Afghanistan only 44 percent of female youth were literate in 2022 compared with 83 percent of male youth (Figure 3.2). In the Central African Republic and Chad, less than one in three young women are literate.

Numeracy skills often lag even further behind literacy skills. In a sample of 13 sub-Saharan African countries, the proportion of children aged 7–14 with foundational numeracy skillsb ranges from less than 1 percent to approximately 36 percent for both boys and girls.28 Limited access to resources, digital technology and skilled teachers exacerbates the situation in rural areas.29 School curricula and textbooks may downgrade farming as an occupation, marginalizing agriculture in young people’s aspirations, contributing to the deskilling of youth and their unpreparedness for life in transforming rural areas.30, 32 For instance, almost no mention of pastoralism is made in Kenya’s educational curriculum.33

©FAO/THAN RATHANY IN SVAY LUR, CAMBODIA, A WOMAN FARMER HARVESTS VEGETABLES

VOCATIONAL EDUCATION AND TRAINING

In many low- and middle-income countries, even students who attend school often leave without the skills required for better remunerated on- and off-farm jobs, creating a disconnect between education and local labour market demand. Technical and vocational education and training (TVET) – with its focus on practical, work-related skills, such as how to process and package food, or training on the cultivation of new or specific varieties of crops – is often promoted to help address skills gaps and increase the employment opportunities of both youth and adults. However, participation in TVET remains limited. Globally, only 13.6 percent of youth (aged 15–24) have completed vocational education, a proportion that decreases to 9 percent in Africa.34 Youth from marginalized groups may face significant barriers to accessing vocational training.

A systematic review based on 37 studies from India found that despite government efforts, participation of youth from tribal communities in vocational training remained low.35

In both TVET and general education, the socioemotional and problem-solving skills needed for successful youth employment, along with necessary advanced cognitive and technical skills, are not being taught.36, 38 Employers highlight the absence of socioemotional skills as the primary reason for their reluctance to hire recent graduates.36 Teaching non-cognitive (soft) skills is likely to be a low-cost investment with high returns, as discussed in Chapter 7.39, 40

However, access to education and training is not sufficient to ensure a match between the skills and training youth receive and those needed for employment. As Fox and Ghandi note, “Africa has both an over-skilling and underskilling problem”,39 which can result in large shares of youth in low- and middle-income countries reporting unemployment or lack of use of their skills. In a sample of eight sub-Saharan African countries, 47 percent of employed youth were overqualified for their jobs, while 28 percent were underqualified,41 pointing to the existence of substantial labour market frictions (see also Chapter 4).

Learning goes beyond formal schooling.42 This is particularly important for rural youth who tend to be disadvantaged in access to quality formal education.30, 32 In rural areas, especially in agriculture, knowledge is often passed down from older to younger generations, starting early as children help on the farm. However, in rapidly evolving contexts shaped by factors such as economic development and improved access to education, young people spend less time at home with family and elders, engaging in traditional agricultural activities. On the other hand, young farmers increasingly aspire to adopt modern, technology-driven agricultural practices.43, 44 Agricultural extension systems can play a vital role in filling this gap, providing access to information and cutting-edge technologies.

AGRICULTURAL EXTENSION AND ADVISORY SERVICES

Agricultural extension and advisory services are integral to equipping those working in agrifood systems with the knowledge and skills necessary for achieving sustainable production. They can take many forms including access to information, financial services, digital platform and marketing support, designed to meet a wide array of objectives beyond productivity gains.45

Recent studies highlight a modest level of youth participation in agricultural extension and advisory services. In Pakistan, researchers found that youth participation in extension programmes plays a critical role in disseminating essential knowledge, promoting sustainable agricultural practices and adopting climatesmart techniques, equipping young farmers with valuable skills and bridging traditional agricultural practices with modern climate adaptation strategies.46 Participation in Farmer Field Schools (FFSs) and other institutional initiatives was also minimal, with disparities observed between male and female youth in case studies from Ethiopia and Nigeria.47, 48 Increasing attention has been paid to targeting youth as both recipients and providers of extension and advisory services,49 though understanding of how to effectively engage youth in extension and advisory services remains limited.

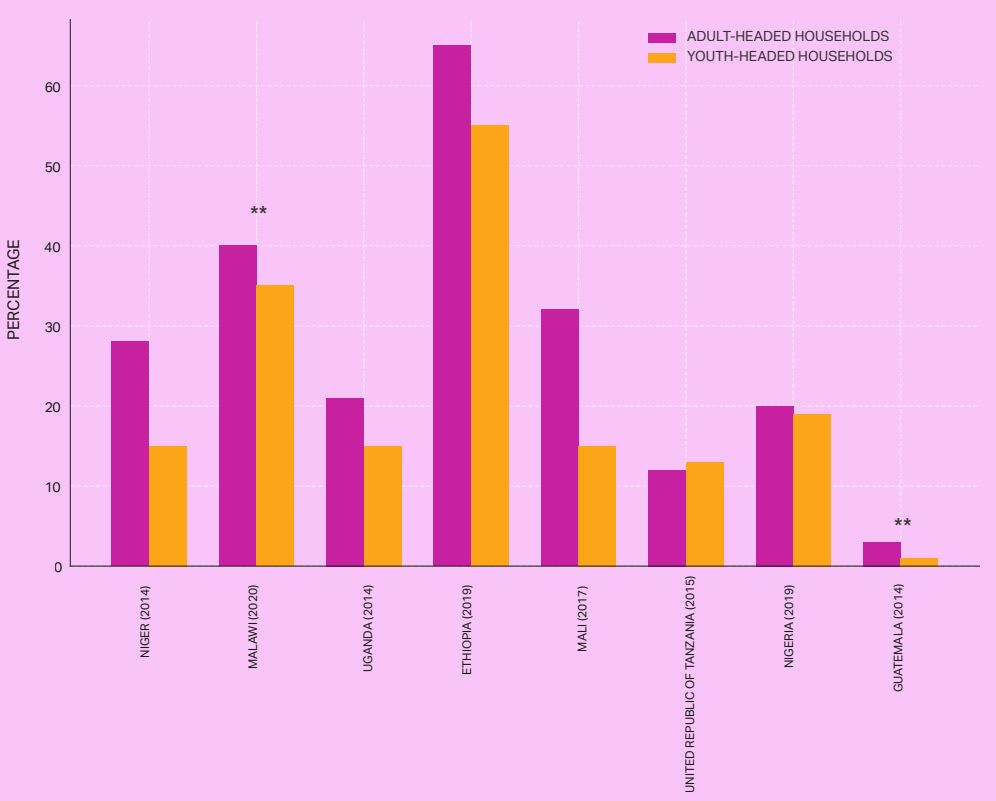

Young men and women are often disadvantaged because extension systems tend to target the household head, who are likely to be mostly older men. Information on access to extension continues to be collected mainly at the household level, resulting in significant gaps in information at the individual level. Even when youth are the head of the household (see Box 3.3), they tend to be disadvantaged in access to extension, as evidenced in Figure 3.3, which shows data from seven sub-Saharan African countries and Guatemala.

RECENT STUDIES HIGHLIGHT A MODEST LEVEL OF YOUTH PARTICIPATION IN AGRICULTURAL EXTENSION AND ADVISORY SERVICES.

Figure 3.3

YOUTH HOUSEHOLD HEADS ARE LESS LIKELY TO HAVE ACCESS TO EXTENSION SERVICES

Share of farming households with access to extension services, comparing households led by young farmers with households led by older farmers, selected countries

Note: The share of youth-led households (out of all households) across the sample of countries is less than 5 percent, but it varies from 0.18 percent in Georgia to 7.7 percent in Malawi. The number after each country name refers to the year of the survey. Countries ordered by increasing level of per capita GDP. Farming households only. Youth = 15–24. Significance: *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.10.

Source: Author's own elaboration based on data from FAO. 2024. RuLIS – Rural Livelihoods Information System. In: FAO. Rome. [Cited 5 December 2024]. http://www.fao.org/in-action/rural-livelihoods-dataset-rulis/en

Box 3.3

YOUTH-HEADED HOUSEHOLDS

The majority of young people aged 15–24 live in households with their parents and depend on their families for their survival and livelihoods. Data from the ILO’s School-to-Work Transitions Surveys, conducted in 34 developing countries across four regions between 2012 and 2016, show that while most young people are still dependent on their parents at age 15, with 80 percent identifying themselves as sons or daughters, this proportion falls to 45 percent by age 24. During this transitional period, the majority of young people are single, living at home and sometimes still studying and/or working in the family business. By age 25, those who are heads of household or spouses outnumber those still considered dependants, although in some countries they may continue to live in the same extended household. By age 29, most young people are assuming adult responsibilities, such as managing their civil status, livelihoods, and family and household duties, including parenthood.i

The proportion of young people with children also increases with age. At age 15, very few report having children, but by age 20, this proportion rises to nearly 20 percent, and by age 25, about 35 percent of young men have children. The trend is more pronounced among women: over 60 percent of young women have children by age 25. This difference is due to the fact that women tend to marry and have children earlier than men. The transition to parenthood, especially if unplanned, has a significant impact on labour market outcomes. Those with children tend to leave school earlier and have higher rates of not in education, employment or training (NEET), with the impact being more pronounced for young mothers.i

Households headed by younger people, including children and orphans, are particularly common in contexts affected by conflict, epidemics, family disruption and poverty. In these situations, older siblings often assume caregiving roles in the absence of adults. Leading such households poses unique challenges that affect both the psychosocial well-being and socioeconomic conditions of young people. Youth heads experience high levels of depression and social isolation, which hinder their ability to care for dependants,ii affecting in turn the development of younger family members.iii In South Africa, older orphans often drop out of school early to support their families.iv The lack of adult guidance also impacts the educational attainment of youth heads who struggle to balance caregiving and schooling.v Because young heads lack the resources and skills to effectively manage needs, these households are more likely to face food insecurity and economic vulnerability.vi Factors such as land rights and inheritance, which are shaped by legal and social norms that do not favour youth, also affect the sustainability of youth-headed households, limiting their ability to generate income and secure a stable livelihood.vii

Gender dynamics in youth-headed households affect decision-making and the distribution of resources. Young heads, especially women, often face challenges related to autonomy in decision-making, including on health-related behaviour due to the weight of gender norms and practices and access to education, which are critical to improving their economic situation.viii Evidence shows that higher educational attainment improves the welfare of these households, leading to better health and economic stability.xi-x

Notes: Refer to the Notes section for full citations.

Important complementarities exist between extension services and education. Extension has been found to be most effective in areas with high levels of education, and less effective where education is low.25 Innovative approaches within extension systems may be needed to overcome the constraints to extension imposed by poor education. Non-traditional approaches – peer-to-peer learning, participatory approaches and practice-based learning on the job or in the field – can supplement the gaps left by the formal education system and extension and advisory services (EAS).

Different models are emerging to include youth in agripreneurship schemes. For example, in Rwanda and Uganda, multiple models have been identified that can support youth engagement in training and entrepreneurship in agrifood systems.49 Models which focused on fee-based service provision by youth as village agents proved more successful. Such models empower youth to operate as entrepreneurial service providers, incentivizing their involvement through financial gains, while meeting the needs of their communities and simultaneously creating localized, sustainable systems for delivering agricultural services.

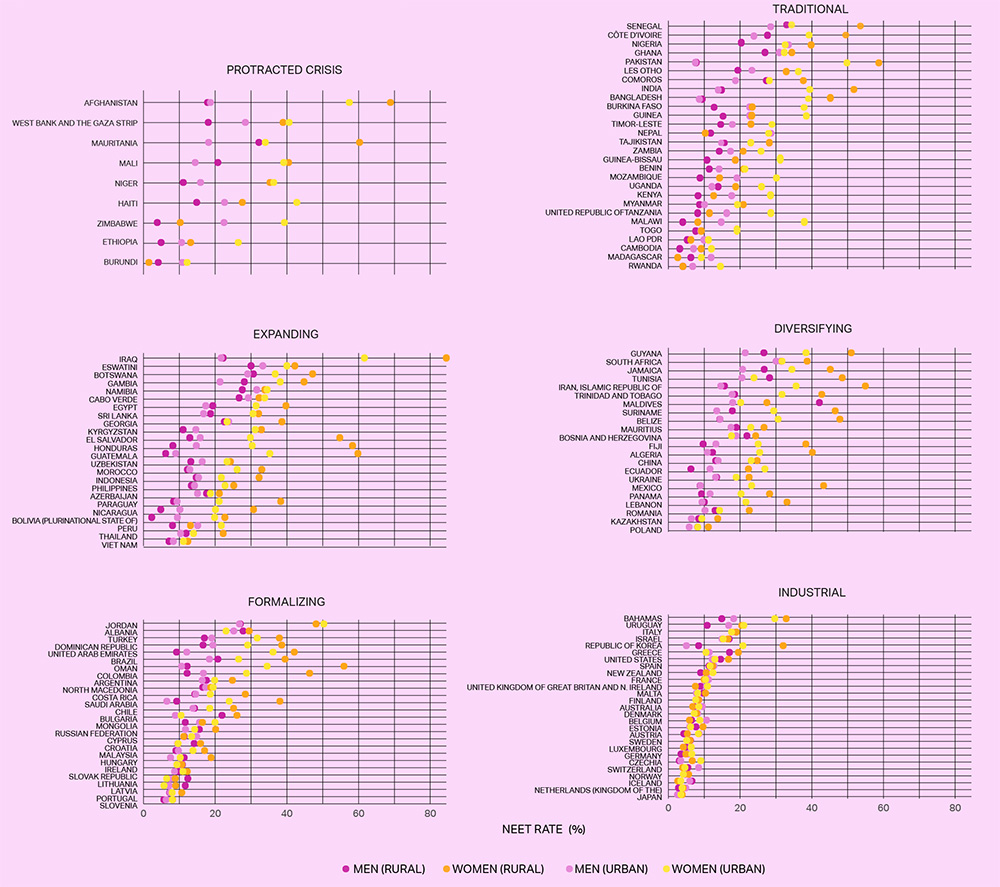

IN 2023, WOMEN ACCOUNTED FOR TWO-THIRDS OF YOUTH CLASSIFIED AS NEET.

YOUTH NOT IN EMPLOYMENT, EDUCATION OR TRAINING (NEET)

Over 20 percent of young people globally were not in education, employment or training (NEET) in 2023.50 Young people categorized as NEET are a highly diverse group facing different constraints and needs in terms of support for effective integration into the labour market.

OVER 20 PERCENT OF YOUNG PEOPLE GLOBALLY WERE NOT IN EDUCATION, EMPLOYMENT OR TRAINING (NEET) IN 2023.

This diversity extends to their vulnerability to social and economic exclusion. A larger share of young women than young men are NEET. In 2023, women accounted for two-thirds of youth classified as NEET.50 In South Asia, the NEET rate among young women was 42.4 percent, nearly four times higher than that of young men.50 Figure 3.4 shows the share of young men and women categorized as NEET across agrifood system transition types. A large share of youth in countries in protracted crisis are defined as NEET, though there is substantial variation across countries and by gender. Young women are more likely to be NEET across the whole sample, with gender gaps disappearing only in industrial systems. Rural young women are significantly more likely to be NEET than their urban counterparts in agrifood systems that are expanding, diversifying and formalizing. However, they are less likely to be NEET in contexts of protracted crises and have similar NEET rates to urban young women in traditional agrifood systems. Young migrant women, particularly those who have migrated to rural areas, are the most likely to fall into the NEET category. For young women, being classified as NEET during youth often results in cumulative disadvantages throughout their lives, reducing their likelihood of employment in later years.

Figure 3.4

YOUNG PEOPLE ARE OFTEN OUTSIDE EMPLOYMENT, EDUCATION OR TRAINING, PARTICULARLY YOUNG WOMEN

Share of youth not in education, employment or training (NEET) by sex across agrifood systems typologies

Source: International Labour Organization. 2020. “Labour Force Statistics database (LFS)”. ILOSTAT. https://ilostat.ilo.org/dataShare of youth not in employment, education or training (NEET) by sex and rural/urban areas(%), ILO modelled estimates, November 2020. Unweighted means.

Greater unpaid and domestic care responsibilities keep young women in NEET, particularly in low- and middleincome countries. Data from 126 countries showed most young women of NEET status were not seeking employment for personal reasons, such as illness, disability, pregnancy, caring for young children or family restrictions.50 In many countries, a large share of young women (20–24 years old) are married before they turn 18, which often results in the end of education and the start of childbearing as well as increased household responsibilities. Early marriage is most common in countries with lower levels of GDP per capita, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa followed by South Asia. Recent research, however, highlights a high prevalence in Latin America and the Caribbean, where one in four girls are married before they are 18 years old.51, 52 Poverty, restrictive gender norms, traditional beliefs and genderbased violence are key risk factors which increase the probability of early marriage.51

Climate change and other shocks are expected to

exacerbate these challenges (see also

NATURAL CAPITAL: LAND, LIVESTOCK AND FISHERIES

LAND

Farming requires land. An extensive body of literature points to land access and secure rights over land as key factors influencing young people’s engagement in agriculture in low- and middle-income countries.29, 57, 58 For example, a lack of access to land, rather than a lack of interest in agriculture, drives Indonesian youth’s aspirations away from agricultural livelihoods.59 In Ethiopia, larger than expected land inheritance increased employment in agriculture, reduced employment in the non-agricultural sector and reduced the likelihood of permanent migration among Ethiopian rural youth.60 Similar patterns were documented in Nigeria,61 suggesting that improving access to land can open-up opportunities for youth in agriculture.

FEW YOUNG PEOPLE OWN ANY AGRICULTURAL OR NON-AGRICULTURAL LAND.

Figure 3.5

FEW YOUNG PEOPLE OWN ANY LAND

Land ownership by sex, age and location

Notes: The figures show self-reported ownership of any agricultural or non-agricultural land, excluding housing. Left-hand bars show land ownership among women; right-hand bars show land ownership among men, across three age groups—Youth (15–24), Young Adults (25–34), and Adults (35–49)—in rural and urban areas. In Nepal, for Young Adult Women and Older Adult Women please note that the share of rural and urban landowners is almost identical, thus the darker color represents both groups. The male individual module was not implemented in Bangladesh, the Philippines and Tajikistan. The countries are arranged by GDP per capita (PPP), ranked from lowest (bottom) to highest (top).

Source: Author's calculations based on data from 26 Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS), http://www.dhsprogram.com/data

Across a sample of 26 countries, few young people own any agricultural or non-agricultural land (Figure 3.5). Timor-Leste is notable for high land ownership among rural youth – over 75 percent of rural young women and 85 percent of young rural men own some land. On the other end of the spectrum are Jordan and Nepal where less than 5 percent of both young men and women, rural and urban, own any land. Land ownership increases with age in all countries. This rise continues until aging adults begin transferring land through sales or bequests to the next generation, at which point it declines.62-63 Given age-related data limitations (women over 49 are not surveyed in Demographic and Health Surveys [DHS]), this trend is not visible in Figure 3.5; however, in higher-income countries, the land area owned by older people increased over time, while transfers of land happened later in life.63, 64 This could be linked to a lack of successor, difficulty selling the farmland or other socioeconomic constraints that hinder generational renewal in agriculture (see Spotlight 1.1). In many countries, youth aged 15 to 17 may not be legally permitted to own land independently until they reach the legal age of adulthood. In some cases, land may be held in trust until they come of age, while in others, minors may be allowed to own land under specific conditions, such as inheritance. Land ownership laws vary by country, and youth land ownership statistics should be interpreted with these legal considerations in mind.

Land ownership is more common among rural young people than their urban peers. A rural–urban land gap is evident across all age cohorts, reflecting the greater reliance of rural populations on land for their livelihoods. The low incidence of land ownership among rural youth is not surprising; many rural young people work on family farms (see Chapter 4), and they may not be given independent plots of land until later in life or upon marriage. Marked gender inequalities in land ownership exist for all ages but are more pronounced for older age cohorts.

Young people who want to farm face constraints to accessing land. In many contexts, particularly in subSaharan Africa and parts of Asia, a smaller share of young people are inheriting land due to increasing land scarcity, and those who inherit land, tend to receive it later in life as life expectancy increases.65 In Ethiopia, young people are less likely than their parents’ generation to be able to access land independently, resulting in different patterns of land acquisition and livelihoods.66 A large number of rural youth grow up without any prospect of inheriting land because their parents operate small plots of land, or are landless or tenant farmers.60 At the same time, the nature of structural transformation in many lowincome economies offers young people limited off-farm opportunities.

Elders and parents may delay transferring land to young people to retain control and secure their own livelihoods in old age. Land is often the only safety net available in rural areas,66 and aging farmers may delay such transfers until they can no longer work the land.70 This hinders youth from building independent livelihoods, fuelling frustration and conflicts.71 Delayed access to farmland through inheritance means that many young people establish themselves as independent farmers when they are no longer young, although their engagement in farming might have started much earlier.2 The tension between young people’s desire to receive land and the desire of older generations to maintain control over their land represents a serious challenge in many rural contexts, including those with customary land systems.72 A case study from Acholi subregion in Uganda, where land is held under customary tenure and is considered to be scarce, revealed that the elders were concerned about transferring land to youth because they feared it would be sold, jeopardizing their old-age livelihood.73 Such fears are exacerbated in the context of land scarcity linked to population growth, urbanization and land degradation, and competing land uses between the expansion of monocrop plantations, tourism development and conservation efforts, as observed in some countries in Southeast Asia.58, 64, 65 In many countries, the promised benefits of plantations have failed to materialize, especially for young people, both in terms of the number and quality of jobs created.76

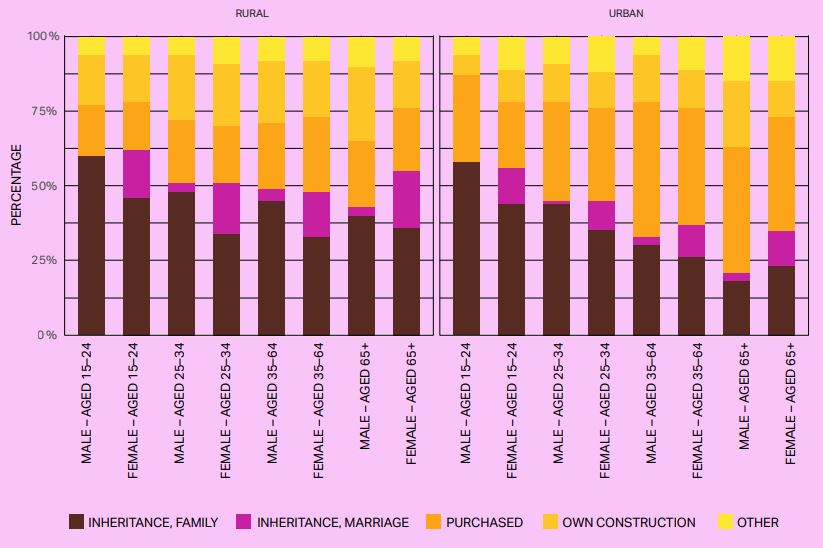

Where land sales are formally forbidden, such as in Ethiopia77 and in customary tenure systems, inheritance is one of the few viable pathways for young people to access land.72 Data from 30 countries on ownership of the main property, which is often a home, show that among both male and female land-owning youth in rural and urban areas, inheritance is by far the main mode of land acquisition (Figure 3.6). The role of inheritance reduces with age as other modes of land acquisition like land purchases increase. Land purchases are less common in rural areas compared to urban areas.

INTERGENERATIONAL TENSIONS OVER LAND ACCESS POSE A SIGNIFICANT CHALLENGE IN MANY RURAL AREAS.

© ALEX WEBB/MAGNUM PHOTOS FOR FAO IN NUEVO SONORA, MEXICO, YOUNG WOMEN PREPARE FOOD FOR A VILLAGE MEAL.

Figure 3.6

YOUNG PEOPLE, BOTH MEN AND WOMEN, ACQUIRE LAND MAINLY THROUGH INHERITANCE

Mode of land acquisition among landowners, by age group and gender

Note: The statistics do not differentiate between residential, agricultural and other land

Source: Author's own elaboration based on Prindex (2020) data for 30 countries with information on types of land acquisition.

Patriarchal customs and laws often favour men in inheritance, amplifying the barriers to land access for young women. Young men and women tend to have different expectations of inheritance. For example, while 40percent of Burundian young men expect to inherit land, only 17 percent of young women hold this expectation.67 Female youth are also less likely than male youth to inherit property from their family but may become landowners through marriage (Figure 3.6). Their access, however, is mediated by gendered power dynamics and patriarchal norms, and their land rights to the property can be lost upon divorce or spousal death.78

Even when equality in inheritance is safeguarded under the law, local norms and traditions may discourage women from claiming their rights. For example, evidence from India suggests that while women’s and girls’ inheritance rights are protected by law and registered on the land record, male siblings took over the inherited land.79 Women tend to relinquish their share of inherited land in favour of their brothers to help them build their independent livelihoods, but also to secure their support or because of social pressure.79, 80 In Kenya, married daughters are refused inheritance to prevent the transfer of land outside their natal holdings and into the husband’s.81

For young people, rising land prices, limited savings and restricted access to credit are key obstacles to purchasing land. The growth of plantations, extractive industries and residential developments tend to fuel increasing land prices, impeding young people’s access to land.29, 72, 76 Community elders and parents may also hold onto land to profit from increased land values brought about by commercial agriculture interests and urbanization.72 Using data from 36 countries at different levels of structural and rural transformation stages, Heckert et al.82 found that rural transformation – proxied by agriculture value added per worker – is associated with reduced likelihood of landownership among both young men and young women, which may be due to increasing land values, increased commercialization of agricultural production, land consolidation and/or migration. The study also showed that higher levels of structural transformation – proxied by the share of GDP from nonagriculture – are associated with a higher likelihood of landownership for young men, but not young women.82

Renting is becoming an important channel through which young people can gain access to land. A larger share of younger household heads rent land than older heads.65 Based on evidence from Canada, China, India and Indonesia, Srinivasan and White (2024) find that most young people are landless and start farming on rented land, even if their parents own land. The only exceptions are youth from land-rich families and those orphaned at a young age.2 A study in Northern Ethiopia similarly found that land rental markets can enhance access to land for landless and land-poor youth.72 However, the study also revealed that male youth, particularly those who owned oxen, were more likely to benefit from these opportunities. Most rental contracts were under a share-cropping arrangements rather than fixed-cash payment, suggesting the existence of financial barriers or risks considerations that influence the willingness and ability of youth to engage in rental markets. In Indonesia too, youth perceived renting land for fixed-cash payment as risky and lamented the increasing scarcity of sharecropping opportunities.83

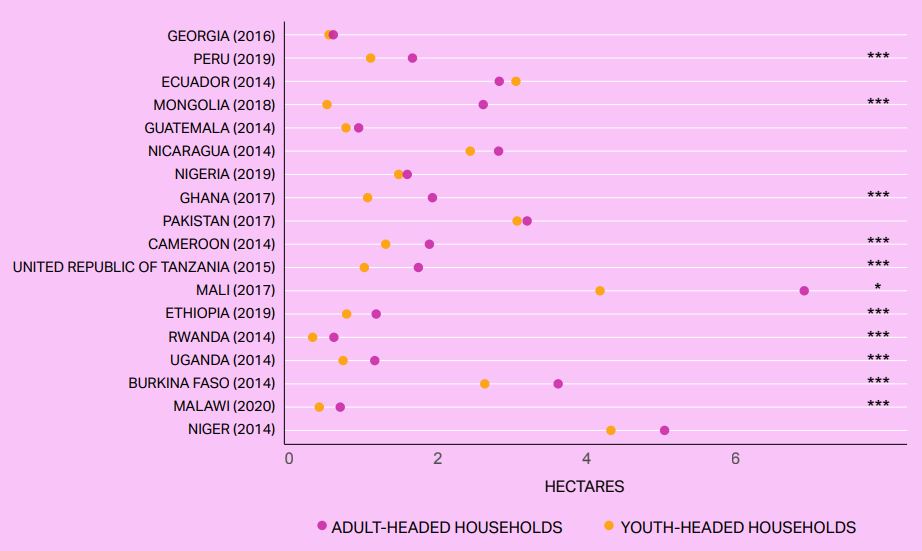

Moreover, when young people can access land, they are often restricted to small plots, which limit their ability to generate a decent income. Households headed by a young adult generally operate smaller farms (see Figure 3.7) compared to older headed households, suggesting that farm expansion and land accumulation often occur progressively over the course of an individual’s life. In a case study from a customary tenure regime in Ghana, over three-quarters of youth respondents expressed dissatisfaction with their land sizes, citing concerns that the plots were too small to sustain viable livelihoods.72 Similar findings are reported in southern Ethiopia.57 In Ghana, young women were only able to access significantly smaller plots.72

©FAO/JAVID GURBANOV IN TOVUZ, AZERBAIJAN, A BENEFICIARY OF THE WOMEN'S EMPOWERMENT PROJECT AND TWO YOUNG MEN STAND IN A WHEAT FIELD, CLOSELY EXAMINING THE WHEAT HEADS.

Figure 3.7

YOUNG FARMERS GENERALLY OPERATE SMALLER FARMS

Average farm size of households led by youth farmers compared to older farmers

Note: Countries are ordered by GDP per capita. The share of youth-led households (out of all households) across the sample of countries is less than 5 percent but varies from 0.18 percent in Georgia to 7.7 percent in Malawi. *** p<0.01, **p <0.05, * p<0.10.

Source: Author's own elaboration based on data from FAO. 2024. RuLIS – Rural Livelihoods Information System. In: FAO. Rome. [Cited 5 December 2024] http://www.fao.org/in-action/rural-livelihoods-dataset-rulis/en

Additionally, young people are more likely to experience tenure insecurity. Youth landowners (aged 15–24) and young adult owners (aged 25–34) experience significantly greater tenure insecurity compared to landowners over 35 years old, with variation across agrifood systems (Figure 3.8). Specifically, youth and young adults encounter significantly higher tenure insecurity than adults aged over 35 in protracted crisis, traditional and expanding agrifood systems, while youth who own land do not experience notably higher tenure insecurity than adults in formalizing and industrial agrifood systems. The lower tenure insecurity among youth (aged 15–24) compared with young adults (aged 25–34) in industrial and formalizing agrifood systems may reflect the longer time youth spend in schooling and their continued financial dependence on their parents in these systems. As they transition into employment, they begin to experience tenure insecurity, closely linked to financial and job instability in early career stages. Youth in rural areas are not any more tenure insecure than their urban counterparts. Female youth also do not report higher perceptions of tenure insecurity than male youth except in formalizing agrifoods systems.

Youth voices are largely excluded from discussions on land matters, at all levels, including land reforms and large-scale land sales. Qualitative research from several countries and large-scale land acquisition cases reveals that young people often express frustration that land negotiations are dominated by local chiefs and government officials, with some input from their parents, while youth are rarely included.84, 85 However, youth should not always be viewed as vulnerable or excluded from land matters. Local context matters. For example, post-conflict contexts, marked by weakened institutions, often provide opportunities to restructure power dynamics over land, including in customary land systems. In a case study from Northern Uganda, Kobusingye86 found that war strengthened the power of young men to assert their claims over land, often undermining the influence of elders and traditional authorities.

Figure 3.8

YOUNG PEOPLE ARE MORE LIKELY TO EXPERIENCE TENURE INSECURITY

Percentage of adults who feel insecure about their property, by age group

Note: The figure shows the coefficients from a linear probability model. The dependent variable is a binary variable equal to 1 if the individual reported feeling tenure insecure. The base category is older adults aged 35 and above. Other controls include education, marital status, household size, country and year fixed effects. The sample includes 126 485 observations and was created by pooling two waves of Prindex data – 2018/19 and 2024 –restricted to land/property owners (i.e. excluding renters and individuals using a property with or without permission).

Source: : Author's own elaboration based on Prindex data downloaded from: http://www.prindex.net/data, accessed 12 November 2024.

FORESTS

Forests provide an important source of livelihood for many young people, especially in the Global South, in addition to supplying ecosystems services and biodiversity.

There is ample evidence of the role that forests and trees play in alleviating poverty,87, 88 particularly for forest-dependent and forest-dwelling groups, such as Indigenous Peoples, by providing safety nets and helping households cope with shocks.89, 90 Globally, 75 percent of the rural population live within 1 km of forests and depend on them for food, fuel, income and culture. Tenure rights, however, are often insecure, with over 70 percent of forest areas under state ownership.91, 92

Systematic data on young people’s involvement in the forestry sector are scarce. However, case studies suggest that young people’s participation in community forestry and conservation can provide an alternative livelihood option.93 A study in Cameroon found that both young men and women relied to varying degrees on livelihoods strategies which integrated agriculture with a range of forest-based activities, including agroforestry, shifting cultivation and the collection of non-timber forest products (NTFP) and firewood. Even young people who relied on non-forest related sources of income, including wage employment, still depended on forests for food and NTFP.94

Access to and use of forests may be mediated by gender and age differences and inequalities. Among the Karen Indigenous Peoples of Southern Myanmar, who practise a combination of shifting cultivation and cash cropping, young men are involved in clearing and burning forest areas, while young women plant rice and vegetables and gather fruits and herbs for food and medicine as part of their domestic chores.95

Overall, there is growing recognition of the need to involve young people in forest management, especially through community forestry and within Indigenous Peoples’ communities.93, 96, 97 This trend has been reinforced by the increasing participation and visibility of young people in global environmental activism.98-100 However, meaningful participation in forest and community governance can represent a serious challenge for young people,101-103 as intergenerational power and gender dynamics hamper young people’s, particularly young women’s, contribution to decision-making and governance. In their research in Mexico, Robson et al. found that young people wanted more say in community decision-making and that young women in particular felt marginalized and unrepresented, explaining that all the decisions were made by men.96, 104 Similarly, a review of community forest governance in Cameroon found that youth felt excluded from local community management and complained that those in positions of authority were not open to democratic selection process. This eventually led to conflict between young people and adults in the Kongo community.105

Young people from communities that depend on forests, including Indigenous Peoples, often prefer to settle in their communities, if opportunities permit. However, the need for education or better livelihood options leads many young people to migrate. At the same time, studies indicate that many who leave also hope to and choose to return.95, 96, 104 For example, evidence from Indigenous Peoples communities in Myanmar shows a strong link between communities’ physical, cultural and spiritual connection to nature and the forest and young people’s desire to stay or return to their community and contribute to its development.95 Similarly, a study conducted among Mapuche Indigenous communities in the Chilean Andes identified limited access to and daily interaction with forests as a cause of children’s and adolescents’ limited knowledge of forest resources. It also played a role in their migration away from the communities for education and their growing feelings of disconnection from traditional practices and the land.106

SYSTEMATIC DATA ON YOUNG PEOPLE'S INVOLVEMENT IN THE FORESTRY SECTOR ARE SCARCE

However, this relationship is being challenged by increasingly limited access to forests as a result of land acquisitions, a decrease in forested areas on people’s farms and deforestation.106 Although the latest data suggest that the rate of global deforestation is slowing, 47 million ha of primary forests was lost between 2000 and 2020, with agricultural expansion driving much of land-use change.92, 107

LIVESTOCK

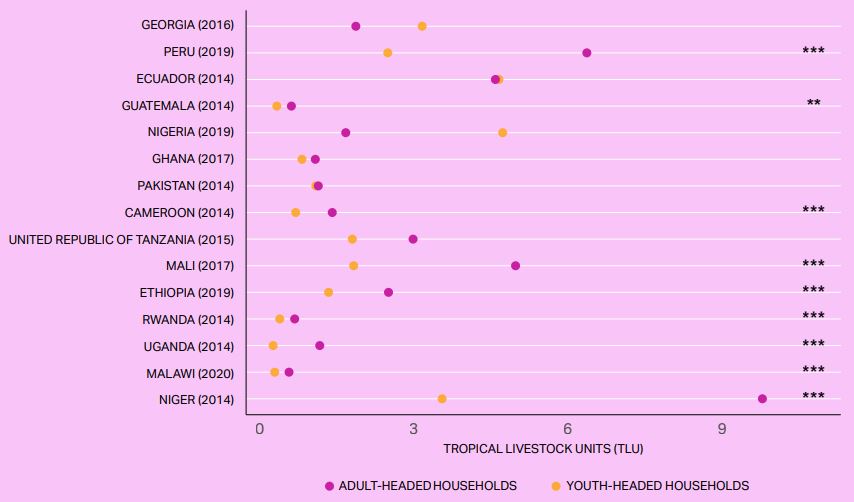

Limited skills, knowledge, land and financial resources, coupled with inadequate policy support, create significant barriers to young people’s involvement in the livestock sector, though it remains crucial for the livelihoods of many young people in agrifood systems.108 National age and sex-disaggregated statistics on individual’s livestock ownership are scarce, making it difficult to estimate young people’s participation in livestock production and their access to livestock as an asset. Case studies suggest that young people encounter challenges in accessing livestock that are considered more valuable and capitalintensive, such as dairy-producing animals.109 As a result, youth-led households have smaller livestock holdings than households led by older adults (Figure 3.9). This is not surprising given youth’s lower access to capital and land.

Figure 3.9

IN MOST COUNTRIES, YOUTH-HEADED HOUSEHOLDS ARE LESS LIKELY TO OWN LIVESTOCK

Average number of tropical livestock units owned by households led by youth compared to older farmers

Note: Countries are ordered by GDP per capita. *** p<0.01, **p <0.05, * p<0.10

Source: Author's own elaboration based on data from FAO. 2024. RuLIS – Rural Livelihoods Information System. In: FAO. Rome. [Cited 5 December 2024]. http://www.fao.org/in-action/rural-livelihoods-dataset-rulis/en

Young people access livestock through inheritance, purchases, gifting and loaning, as well as through the reproduction of animals already owned.110 Livestock acquisition and ownership patterns may be strongly gendered. In Kenya, livestock is mostly inherited by sons. While the inheritance of livestock by girls is unusual and against prevailing norms,110 both men and women may receive livestock as rewards for achievements, and girls may be given livestock to mark important life events such as marriage and the birth of a child.110 However, even when young brides receive such gifts, control over the livestock may reside with the groom. Women often have easier access to and control over small ruminants and poultry, which provide them with an opportunity to earn an income that they can control and an asset that can be sold in the event of shocks.111, 113

Cambodia, Ethiopia, Malawi and the United Republic of Tanzania are among the few countries to collect national, individual-level data on livestock ownership that can be disaggregated by both age and gender, as shown in Figure 3.10. Three elements are apparent from these data. First, a lower share of youth in all countries own each type of livestock, as compared to older adults. Second, young men are more likely than young women to own large livestock in the United Republic of Tanzania, while the opposite is true in Cambodia and Ethiopia. In rural Ethiopia, 26 percent of female rural youth compared with 17 percent of male rural youth own large livestock, either solely or jointly, while among older adults, 80 percent of adult men and 56 percent of adult women own livestock.

The data are consistent with findings in the literature suggesting that access to livestock in Ethiopia is affected by gender, age, marital status, ethnicity and class, and that women’s perceptions of ownership may change as they age.114 Third, in all countries young women are more likely to own poultry compared to young men. In Cambodia, 30 percent of rural young women (aged 18– 24) own some poultry, compared with 17 percent of rural young men.

Norms around youth’s ownership and control over livestock, and their participation in livestock value chains can evolve. For example, in Ethiopia, there is evidence that young women are increasingly able to control income which comes from the sale of sheep and goat products (e.g. cheese and butter), and that young people are working in wage positions in small-ruminant value chains, reducing the importance of owning larger animals.115, 116 In addition, newer strategies are being adopted to facilitate young people’s access to livestock. For example, a study in Baringo County in Kenya found that young women acquired cattle, sheep and goats through participation in rotating savings groups.110 However, among pastoralist youth in Ethiopia, membership in local savings organizations, which seemed a promising approach to enable young people to acquire livestock, was limited by lack of income and social capital.117

FISHERIES AND AQUACULTURE

A review by WorldFish on aquaculture and smallscale fisheries highlights the fact that young workers, particularly young women, dominate employment in the fisheries sector.118 A global survey of aquaculture farms found that most workers were between 20 and 39 years old.119 Similarly, a study on predominantly female workers in shrimp processing factories in Bangladesh reported that 60 percent of workers in the Chittagong region were between 18 and 25 years old.120 In Nepal’s Terai region, a project introducing carp-prawn polyculture technology to small-scale women farmers found that 58 percent of participants were between 20 and 39 years old.121 Meanwhile, in small-scale fisheries, women-led artisanal and invertebrate fishing activities in Al Wusta Governorate of Oman were carried out primarily by those aged 21 to 30, accounting for 34 percent of participants.122

However, youth participation in fisheries and aquaculture is shaped by skills and asset gaps that limit their ability to engage fully in these value chains. While globally comparable data on youth participation in fisheries are not available, case studies show that ownership of, control over and access to assets and technologies influence the propensity of young people to engage in fisheries and aquaculture value chains. Such asset gaps are similar to those that influence the likelihood of youth taking up crop farming. Nets, boats and land for aquaculture are often transferred intergenerationally, over time, reducing access by youth.123 Additionally, in Kenya significant skills gaps limit young people’s participation in the more profitable parts of fish value chains.124 Meanwhile, in the Ugandan catfish industry, a recent study by FAO demonstrates that young people are under-represented in all aspects of the value chain, though better represented in fish processing, a highly feminized segment.125 Youth need to overcome the above-mentioned asset and knowledge gaps in order to capitalize on government incentives in fisheries and aquaculture value chains, as shown in a case study on Nigeria.123

In both sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America, youth’s access to technology such as mobile applications, as well as more advanced technologies like sonar and drones for those with greater economic means, could offset perceived risks related to climate change dissuading them from entering fisheries value chains.126, 128 In the Republic of Korea, specialized female fisherwomen/divers called haenyeo are aging, with most in their mid-60s or older, and are not being replaced by younger women due to the physical strain of the job, which is performed traditionally without the use of oxygen supplies. Economic issues also serve as a barrier to newcomers: younger women were dissuaded from joining haenyeo cooperatives where earnings are shared among a small group of existing fisherwomen.129 Recently, however, a number of initiatives have been created to preserve the tradition and pass on the knowledge to younger generations through haenyeo associations, cooperatives and schools.130 Young haenyeo are also using social media to boost their image and sell their produce.131

YOUNG WORKERS – ESPECIALLY WOMEN – DOMINATE EMPLOYMENT IN AQUACULTURE AND SMALLSCALE FISHERIES.

Figure 3.10

ACROSS ALL COUNTRIES, FEMALE YOUTH ARE CONSISTENTLY MORE LIKELY THAN MALE YOUTH TO OWN POULTRY, WHILE GENDER PATTERNS IN OWNERSHIP OF OTHER LIVESTOCK VARY

Incidence of livestock ownership among men and women of different age groups in Cambodia, Ethiopia, Malawi and the United Republic of Tanzania

Source: Author's own elaboration based on the LSMS+ surveys for Cambodia and Malawi and LSMS-ISA surveys for Malawi and the United Republic of Tanzania

FINANCIAL CAPITAL

FINANCIAL INCLUSION FOR YOUTH

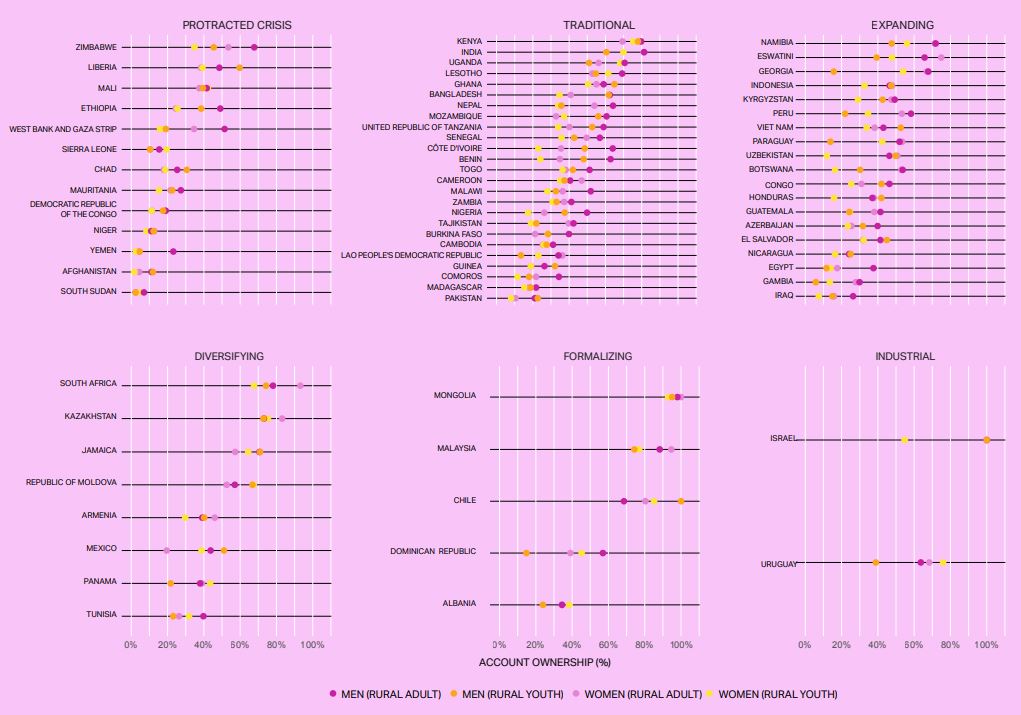

Youth (ages 15–24) are disproportionately unbanked, particularly in low- and middle-income countries. In subSaharan Africa, for example, nearly 40 percent of the unbanked population consists of young adults in this age group. Globally, in 2021, 66 percent of youth aged 15–24 owned a formal financial account, compared to 79 percent of individuals over 25 years.132

In rural areas, youth – particularly young women – are significantly less likely than their older counterparts to own a financial account (including both financial institutions and mobile money). This gap is most evident in protracted crisis and traditional agrifood systems, where financial services are often underdeveloped or inaccessible (Figure 3.11). The share of young women with a financial account is effectively zero in countries such as Afghanistan, South Sudan and Yemen, and does not exceed 40 percent in any of the countries with protracted crisis agrifood systems (Figure 3.11). Account ownership among rural young women is higher in countries in traditional and expanding agrifood systems, reaching over 50 percent in Georgia, Ghana, India, Kenya, Lesotho, Namibia and Uganda. Account ownership tends to increase as agrifood systems transition, but with significant heterogeneity among countries, and a higher share among young rural women in some cases.

A key structural barrier to youth financial inclusion is age-related legal restrictions. In many countries, young people under 18 are unable to open bank accounts or take out loans independently, limiting their ability to save, invest and participate in economic activities. To address this barrier, several countries are exploring regulatory reforms to expand youth financial access. In Uganda, the National Financial Inclusion Strategy (2017–2022) recommended lowering the minimum age to open a savings account to 15 years. The Central Bank of Jordan is considering similar reforms to allow youth as young as 15 to open accounts without a legal guardian’s approval.133

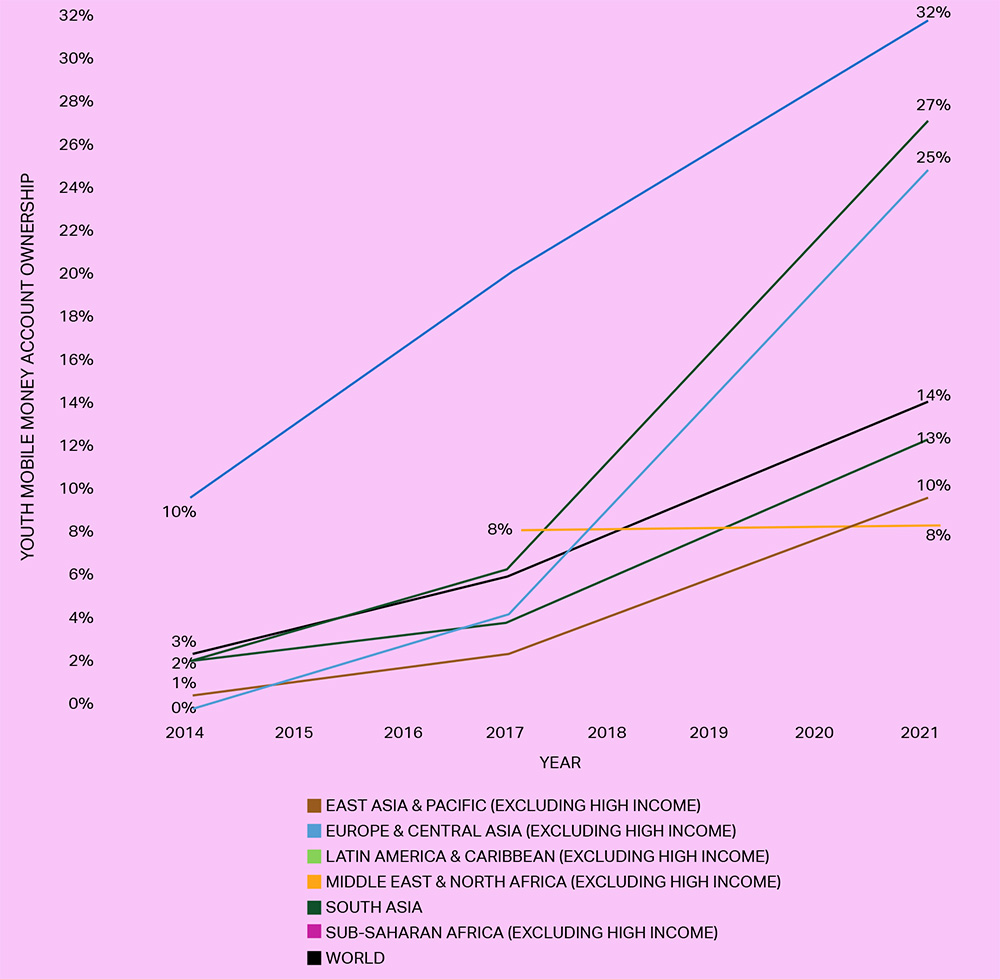

In contexts where the formal financial infrastructure is either lacking or inaccessible, mobile money offers an efficient and affordable alternative for youth to access financial services. In sub-Saharan Africa, for example, 32 percent of young people had a mobile money account in 2021 (see Figure 3.12), followed by Latin America and Caribbean and Europe and Central Asia with 27 percent and 25 percent, respectively. Countries with traditional agrifood systems (e.g. Ghana and Kenya) tend to have higher rates of mobile money adoption among both youth and adults, reflecting the low accessibility of formal institutions.

Conversely, countries with protracted crisis agrifood systems tend to have lower overall adoption, indicating barriers such as weak or disrupted infrastructure, and economic instability. Expanding and diversifying agrifood systems show more mixed trends, with some countries exhibiting relatively balanced adoption rates across age groups (Figure 3.13). Similarly, youth access to mobile money accounts has increased in all regions since 2014 (Figure 3.12).

YOUTH ARE DISPROPORTIONATELY UNBANKED, PARTICULARLY IN LOW-AND MIDDLE-INCOME COUNTRIES.

Figure 3.11

A LARGE SHARE OF RURAL YOUTH DO NOT OWN A FINANCIAL ACCOUNT

Ownership of any financial account (financial institution and mobile money), by age group and gender

Note: The full dataset includes information from 139 countries, collected in 2021 and 2022; however, only 72 countries provide rural–urban disaggregation. The results here are restricted to those 72 countries.

Source: Author's own elaboration based on data accessed from the Global FINDEX Database 2021.http://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/globalfindex/Data

Access to mobile phones and the internet are among the key factors driving the uptake of financial services among young people.134 Research shows that gender gaps in youth financial inclusion can be attributed to varying levels of digital technology endowments. Youth with mobile phones are three times more likely to have financial accounts and three and a half times more likely to use them, with internet access doubling this likelihood.135 However, gender and rural–urban disparities remain a significant challenge to youth financial inclusion. For example, Bangladesh faces a widening gender gap, affecting especially low-income women and those residing in rural areas. Young women with lower access to digital connectivity at the outset of their financial inclusion journey are adversely affected, disadvantaging their lifelong financial inclusion.134 A more in-depth overview of digital inclusion of young men and women is provided in the next section.

ACCESS TO MOBILE PHONES AND THE INTERNET ARE AMONG THE KEY FACTORS DRIVING THE UPTAKE OF FINANCIAL SERVICES AMONG YOUNG PEOPLE.

Figure 3.12

YOUTH ACCESS TO MOBILE MONEY ACCOUNTS HAS INCREASED IN ALL REGIONS

Youth mobile money account ownership across regions, 2014–2021

Source: Author's own elaboration based on the individual-level data from The Global FINDEX Database 2021. http://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/globalfindex/Data accessed 12 September 2024.

Figure 3.13

MOBILE MONEY ACCOUNTS ARE POPULAR AMONG BOTH YOUTH AND ADULTS IN MANY COUNTRIES IN TRADITIONAL AGRIFOOD SYSTEMS

Note: The sample includes information from 139 countries, with information collected in 2021 and 2022, but only 72 countries provide rural–urban disaggregation. The results here are restricted to those 72 countries.

Source: Author's own elaboration based on individual 2021 FINDEX data.

PHYSICAL CAPITAL

DIGITAL INCLUSION

Digital technologies are rapidly emerging as a means to achieve smarter, more efficient, sustainable and resilient agrifood systems.137 new opportunities for young people, often previously underserved by face-to-face service providers,138, 139 to increase their access to information, training and marketing opportunities.140-142 Furthermore, digitalization has helped reshape perceptions of agriculture, making the sector more appealing to younger generations.143-145 While more data are available about youth access to digital technologies and ICTs than about many other assets, additional research is needed on the impact and determinants of digital technology adoption by youth in agrifood systems, taking into consideration age specificities as well as intersectional challenges linked to socioeconomic characteristics including gender, ethnicity and educational background.

Globally, youth are more digitally connected than older populations, with 81.2 percent of young people aged 15–24 using the internet, compared to 68.2 percent of adults aged 25–74 (Figure 3.14). In industrial agrifood systems, 98.2 percent of youth use the internet, whereas in traditional systems, only 33.9 percent have internet access. However, the share of youth in traditional systems using the internet is nearly 40 percent higher than their adult counterparts. This digital divide between youth and adults narrows as countries transition from traditional to industrial agrifood systems. Thus, while young people in LMICs are more likely than older generations to use digital technologies, poor infrastructure and affordability constraints continue to limit their ability to fully leverage these opportunities.146 Few youth in LMICs have access to internet at home. In 2020, only 5 percent of rural youth and 13 percent of urban youth in low-income countries had internet access at home, compared to approximately 90 percent of youth in high-income countries.147

While reducing the coverage gap in broadband connectivity and increasing the affordability of internet data remain an issue in rural and remote areas,148, 149 internet access is only one of a set of barriers to rural youth’s digital inclusion. Socioeconomic, behavioural and cognitive challenges lead to unequal access to digital devices, unaffordable services, limited digital skills, lack of awareness and usability of digital services, and safety and security concerns.150, 151 As a heterogenous group with varying levels of education, skills and household wealth,68 rural youth experience these barriers in different ways. For example, adolescent girls and young women are particularly limited in their ability to participate in the digital world, due to restrictive social norms and deep-rooted structural inequalities, such as lower education and income. For every 100 male youth aged 15–24 who have digital skills, only 65 female youth do.152 Moreover, evidence from LMICs reveals that girls gain access to digital technology at an older age and are more supervised or restricted from using computers or mobiles than boys.153 Another commonly reported “after-access” barrier is the lack of youth-friendly digital services or content available in local languages for those youth who are not conversant in English or other widely used languages.

IN 2020, ONLY 5 PERCENT OF RURAL YOUTH AND 13 PERCENT OF URBAN YOUTH IN LOW-INCOME COUNTRIES HAD INTERNET ACCESS AT HOME.

Despite these constraints, youth are typically more tech-savvy than adults and are uniquely positioned to leverage digital technologies to increase the productivity, profitability, sustainability and resilience of farms and agribusinesses.50, 154Digital technologies not only facilitate access to information, they are also revolutionizing agricultural practices allowing young farmers and agripreneurs to engage in contract farming, direct marketing, logistics coordination, networking and access to funding opportunities.155 Technological innovation helps to attract young people who would ordinarily not be interested in farming, including welleducated urban youth.156, 157

FOR EVERY 100 MALE YOUTH AGED 15—24 WHO HAVE DIGITAL SKILLS, ONLY 65 FEMALE YOUTH DO.

Figure 3.14

YOUTH ARE MORE LIKELY TO USE THE INTERNET THAN ADULTS, EXCEPT IN PROTRACTED CRISIS AGRIFOOD SYSTEMS

Youth internet use vs adult population, by agrifood system typology

Note: The estimates are weighted means, with weights adjusted for the population size of each country. The dataset includes the proportion of individuals who used the internet from any location in the last three months, covering internet usage statistics for individuals aged 15–74 across 107 countries.

Source: Author's own elaboration based on data from the ITU (International Telecommunication Union) DataHub (https://datahub.itu.int/data/?e=ITA&c=701&i=11624&d=Age&g=9224) accessed 5 March 2025.

Youth in agriculture are utilizing digital agricultural solutions. Out of a sample of 30 000 youth engaged in agriculture across 11 African countries, 23 percent were found to be engaging with at least one form of digital agricultural technology (an app, SMS, website or software). According to respondents, ease of use, range of information provided and affordability are three critical success factors of digital solutions.158